By Nokmedemla Lemtur

Published in 2020

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00026

Image: A person hiking in a snowy landscape.

Table of Contents

Germany in the Himalayas | Himalayan porters in the German archive | Abbreviations | Endnotes | Bibliography

The end of the nineteenth century witnessed the start of climbing expeditions in the Himalayas that were distinct from the earlier expeditions that focused on surveying and exploring the region. Euro-American climbers became fascinated with the idea of climbing the world’s highest peaks and in the early twentieth century launched attempts to break the altitudinal record. While the English began their attempts at climbing Mount Everest from 1922 onwards, German climbers launched their Himalayan expeditions with their first attempt to climb Kangchenjunga in 1929. Between 1929 and 1939, Germans undertook eleven mountaineering expeditions to the Himalayan peaks. They were comparable only to the attempts by the British climbing expeditions in the same period.

The Deutsche Alpenverein (DAV – German Alpine Club) and the Deutsche Himalaja-Stiftung (DHS – German Himalaya Foundation) were the two institutions that provided most of the support for these expeditions. The DAV was established in 1869 in Munich for the promotion and support of Alpine tourism. It merged with the Österreichischer Alpenverein (ÖAV – Austrian Alpine Club) in 1873 to form the Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein (DuÖAV – German and Austrian Alpine Club). In 1911, the DAV Museum was set up on Prater Island in Munich and still holds the archive at the same address.[1]

Unlike state or economic archives, the archive of the DAV is a smaller and more specific institution. It is organized in seven holdings (Bestände):

- Archivalien des DAV, des DuÖAV und der Sektionen (Records of the DAV, the DuÖAV and the Sections)

- Historische Dokumente zur Alpingeschichte (Historical documents on alpine history)

- Archivalien der Expeditionsgesellschaften (Archives of the Expedition Societies)

- Fotografien und Postkarten (Photographs and postcards)

- Personennachlässe (Private papers)

- Werbemittel (Advertising material)

- Dokumentationen (Documentations)

Within the framework of Indo-German entanglements, the holding titled Archivalien der Expeditionsgesellschaften is of specific interest, as it holds the files, photo archive, film and audio material of the German Himalayan Foundation (Akten, Fotoarchiv, Film- und Tonmaterial der Deutschen Himalaja-Stiftung). The individual files of this holding originate from the many Himalayan expeditions undertaken during the twentieth century.

This post aims to provide a guide to this specific holding of the DAV archive that documents the beginning of German mountaineering efforts in the Himalayas and, in doing so, highlights a unique facet of Indo-German history as it attempts to uncover traces of the non-elite or native expedition labourers. The first section provides the context and trajectory of the expeditions, highlighting the conditions under which such materials were produced. The second section focuses on the holding in the archive and the various materials that refer to the expeditions’ labourers.

Germany in the Himalayas

The Weimar years (1918–1933) marked a shift in the attitude towards mountains and mountaineering in Germany from recuperative recreation to an assertion of the ideology of the nation. According to Lee Holt, the First World War changed the envisioning of the Alps, as they became “a microcosm of the nation, a geographic site where mountaineers would train the next generation of soldiers” (Holt 2008: 4). The 1920s saw the emergence of the alpine journals of Germany and Austria encouraging people to look to the mountains for strength and inspiration, as the mountains would be the remedy for the sick and weak nation (ibid.). The journals also called for the re-establishment of Germany’s geopolitical presence, so German alpine organizations launched various expeditions beyond their traditional area of activity into the Pamirs and the Himalayas. The new mountaineer embodied a new masculinity that drew upon several different discourses of the Weimar Republic: body, behaviour, morality and spirituality became the quintessential qualities of a mountaineer who frequently represented both the German nation and the promise of an imperial future (Ibid: 81).

It was within this context that German mountaineers started looking towards the Himalayas and marked the beginning of a prolonged effort to conquer Himalayan peaks, in particular two peaks: Kangchenjunga (8598 m) in the eastern Himalayas and Nanga Parbat (8126 m) in the western Himalayas. The first such expedition, led by Paul Bauer, was to Kangchenjunga in 1929. With a team of eight Germans and two Englishmen deputised to the expedition by the British colonial government, it managed to climb to a height of 7,400 meters, but failed to reach the summit. Another expedition in 1930 led by the Austrian Günter Oskar Dyhrenfürth (Die Internationale Himalaya-Expedition (IHE)) attempted the same peak, but, having failed, attempted and succeeded in climbing the neighbouring Jongsong, Ramtang and Nepal peaks. Bauer launched another expedition to Kanchenjunga in 1931, but managed to ascend only to a height of 7,775 m, the highest altitude ever reached by any person at that time. But, just as in 1929 during his first expedition, he again could not reach the peak.

Having failed to scale the third highest peak of the world, there was a shift in focus towards Nanga Parbat in the western Himalayas, to which the Germans felt they had a connection. The discovery of Nanga Parbat is ascribed to Adolf Schlagintweit,[2] who in 1856 travelled this region and noted this particular summit for its towering height, overshadowing all other snowy peaks (Mason 1955: 82). The first climbing attempt is attributed to the British climber A.F Mummery, who tried to scale it in 1895. However, this attempt ended in tragedy with the disappearance of Mummery and the Gurkha soldiers who accompanied him.

In 1932, permission was given to a German-American Himalayan Expedition led by Willy Merkl to climb Nanga Parbat, but it failed to reach the summit, owing to weather conditions and labour troubles. Preparation for another attempt began almost immediately with renewed support from the German government. In 1933, the German Alpine Club was brought under the Deutscher Reichsbund für Leibesübungen, (DRfL – German National Federation for Physical Exercise) (Holt 2008: 265). This move brought the narrative of German mountaineering under the control of the National Socialist party, which had come to power in Germany. The Reich Sports Leader Hans von Tschammer und Osten provided government support to the expedition by applying for and getting approval for the necessary travel visas through British India. Having received greater funding through the Bund der deutschen Reichsbahn-Turn- und Sportvereine (Sports Club of the German State Railways), Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Society for German Scientists) and the DuÖAV, this expedition was the grandest so far in terms of its ability to equip and provide for not only the German climbers but also the Sherpa porters, who were recruited from Darjeeling (Bechtold 1936: xviii). This expedition ended in disaster with the deaths of four German climbers – Alfred Drexel, Uli Weiland, Willo Welzenbach and Willy Merkl – and six Sherpa porters from Darjeeling – Nima Norbu, Nimu Dorje, Dakshi, Gaylay, Pinzo Norbu and Nima Tashi. At that time, reports of what was considered the greatest-ever climbing disaster spread across the world and especially to the German public.

In the German imagination, Nanga Parbat became renowned as the Schicksalsberg – the mountain of destiny (Höbusch 2002). Renewed efforts to climb the peak materialized in the form of the establishment of the German Himalayan Foundation (Deutsche Himalaya Stiftung) under the Ministry of Culture in Bavaria in 1936 (Mierau 1999). The foundation was created to support climbing and scientific expeditions to the Himalayas and marked a new chapter in German efforts to conquer the Himalayan peak, as it provided even greater support for planning such expeditions. In the same year, permission was denied for any expeditions to this region due to the Kashmir Durbar’s apprehensions about such enterprises’ demands on the resources of the land. An expedition to Siniolchu peak in Sikkim was instead organised with Paul Bauer as leader. It succeeded in the first-ever ascent of Siniolchu (6891 m) and other surrounding peaks – Simvu (6550) and Nepal peak (7150 m). A member of this expedition, Karl Wien, became the leader of the next Nanga Parbat expedition in 1937. This attempt turned out to be a bigger disaster than the previous one, with sixteen fatalities (seven German climbers and nine porters). An ice avalanche completely wiped out Camp IV, where the sixteen members had camped.

The disasters of 1934 and 1937 were glorified to the German public in fiction and newspaper publications as the sacrifice of eleven German patriots. Harold Höbusch shows how Ad. W. Krüger’s novel Der Kampf um den Nanga Parbat (The Struggle for Nanga Parbat, 1941) dramatizes the 1934 expedition and puts great emphasis on loyalty and camaraderie (Höbusch 2003: 27). The deaths of the mountaineers were elevated to martyrdom and used for propagandistic purposes after the National Socialist ascent to power in 1933 (Höbusch 2003: 32). Fritz Bechtold’s Deutsche am Nanga Parbat (1935 – Germans on Nanga Parbat), the most famous work of German alpine literature in the first half of the twentieth century, went through twelve editions until 1944 (Holt 2008: 275). Bechtold’s narrative of the 1934 expedition constructed the expedition in line with the fascist ideology of sport. The key components of his book stressed the marshalling of chaos into order, adhered to the Führer principle, depicted “only German” members and used military rhetoric to praise the sacrifice of the individual in serving the nation and disciplining the body (Höbusch 2002). The documentary Nanga Parbat: Ein Kampfbericht der deutschen Himalaja-Expedition 1934 (Nanga Parbat: A Frontline Report on the German Himalaya Expedition of 1934, 1935) was used as propaganda in the Third Reich for over two years and was also shown at the end of the Winter Olympics of 1936 (Holt 2008: 275). There was another expedition in 1938 led by Paul Bauer by another route with the base camp at either Mansehra or Abbotabad.[3] This attempt failed, and so did the subsequent expedition in 1939 led by Peter Aufschnaiter, which was cut short due to the declaration of war between Germany and England.

Himalayan porters in the German archive

Preparation for such expeditions required extensive communication and co-ordination between Germany and the British government in India, which, apart from providing logistical support in the form of loaning transport officers and granting customs exemptions, also acted as intermediaries to the provincial powers in Kashmir and Sikkim. These correspondences form the transnational entanglement at the level of international diplomacy and collaboration between the two countries. Such materials are often located in state archives and make little mention of the porters who were recruited for these expeditions. In the absence of any Indian “climbers”, the porters who carried the loads up the mountains and served the German climbers were the native counterpart in this Indo-German experience. The perceived problem in doing research on this particular group is the paucity of archival material. Very little is known about them. The objective here is to trace evidence of a group of people who were so vital to these expeditions but are hidden from the dominant narratives of mountaineering and labour history.

A clear illustration of the presence of the Himalayan porters is the 1934 expedition to Nanga Parbat led by Willy Merkl, which consisted of thirty-five porters recruited from Darjeeling, five-hundred Kashmiri porters and forty Balti (from Baltistan) porters. The ratio of German climbers to native porters clearly points to the significance of the porters. The challenge is to locate them in the enormous paper trail these expeditions left behind. The holding Archivalien der Expeditionsgesellschaften within the DAV Archive orients the researcher towards a specific intervention in German mountaineering history, as it contains documents of the Deutsche Himalaja Stiftung (DHS). The DHS organized nine expeditions to the Himalayas until 1957. Following this, the DHS was accepted into the DAV and was subsequently renamed Himalaja-Stiftung im DAV (the Himalaya Foundation in the DAV) (Mierau 1999). Thereafter, the Himalaja-Stiftung continued to support various expeditions until its dissolution in 1998. In 1994, the Stiftung’s archive was transferred to the central archive of the DAV in Munich, where it has been compiled under the holding mentioned above; this post looks at the early years of the Stiftung’s operation.

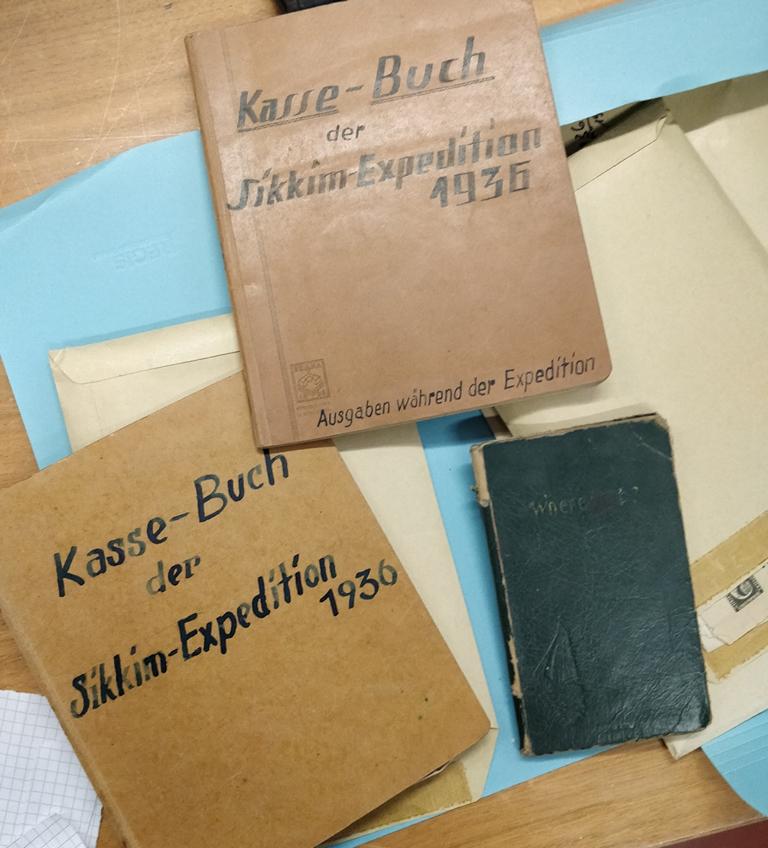

The list of records of the DHS from its conception in 1936 to its dissolution in 1998 is available in the online finding aid https://www.historisches-alpenarchiv.org/ (as are records from other holdings of the DAV). On inputting keywords such as “indien” or “himalaja”, the online finding aid provides a comprehensive list of archival material ranging from written records (Schriftgut) to photographs and maps from the various expeditions. The finding aid provides search results down to specific written or visual records. These documents appear with the signature EXP, which signifies the documents within the holding of the expedition organisation or societies (Expeditionsgesellschaften). More specific keywords like “Merkl” or “Dyhrenfürth” provide further information; their use presupposes a more thorough prior knowledge of specific individuals involved in the expeditions. However, the search results are not an exhaustive list, as some documents in connection with the expeditions are found across other holdings of the archive. An example to illustrate this is the 1936 expedition to Siniolchu led by Paul Bauer. Most of the information pertaining to this is located in the society holding and appears with the signature EXP. However, a report by a member of the same expedition, Fritz Schmitt, is found in the private paper holding (Personennachlässe) under the signature NAS. Further, miscellaneous correspondences can also be found in the holdings of various sections of the archive, which is recognised by the SEK signature.[4]

The holding of the expedition societies is extremely rich in data on various aspects of the expeditions, but to find information on the porters requires a more careful analysis of the material. The records produced by these expeditions can be divided into two broad categories. The first category comprises expedition reports and the official publication of such reports in the form of articles in journals, newspapers and ultimately the published expedition monograph. Such materials are identified by reading files titled “Presse” or “Bericht” (Press material or Reports). The tropes such narratives fall into are comparable to those of travel writings that begin with the traveller’s preparation and description of the journey. As was common in travel literature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the figure of the native appears in anecdotal encounters, and the writers’ description of such encounters became a part of the process of knowledge production. In their investigation of porter relations in the Karakorams, MacDonald and Butz (1998) explain that travel in the Himalayas was regulated by a set of complex and largely tacit rules prescribed by the colonial state, and this largely influenced the relations between the traveller as the sahib and his native companions as the porters or coolies (MacDonald & Butz 1998). This in turn solidified the role that such actors played and limited their ability to transcend this particular position. These authors highlight the crucial point that labour is not a static category in the narratives produced about the experiences of travel, mountaineering and exploration. The changing descriptions of labour reflect the internal agency of the labourers (MacDonald & Butz 1998: 300–301). Such accounts create narratives of the experiences generating knowledge in which the descriptive becomes the normative. These documents are peppered with anecdotes mentioning particular porters, often narrating particular instances, which in turn become part of the corpus that becomes complicit in creating and perpetuating stereotypes. The files containing press material also often mention the porter as part of the logistical data. However, on rare occasions, a larger report on the porters can be found, mostly in the aftermath of a disaster in the mountain.

The second category of archival material is files containing extensive lists of Ausrüstung und Verpflegung (Equipment and Provisions), Finanzen (Finances), Verschiedene Erklärungen (Various Explanations) etc. These records range from thick files containing numerous correspondences and draft lists of food items and equipment to be procured and packed in various boxes for the expedition to payrolls and the distribution of loads during the advance and load-ferrying up and down the mountain. Loose documents detail extensive planning of what kind of food and equipment to be carried not only for the climbers, but for the porters as well. This detailed attention to the provisions provides information on minute aspects of the organisation, but also the desire to prevent any delays in the expeditions, as the most likely cause of labour troubles was insufficient provisions or clothing and equipment. The porter is mentioned often in two categories – Träger and Kuli. The first term directly denotes porter and the second is the oft-used term for unskilled coolie labour in the Indian subcontinent. The documents do not clearly mention a difference between the two and suggest that the terms could have been used interchangeably in these instances.

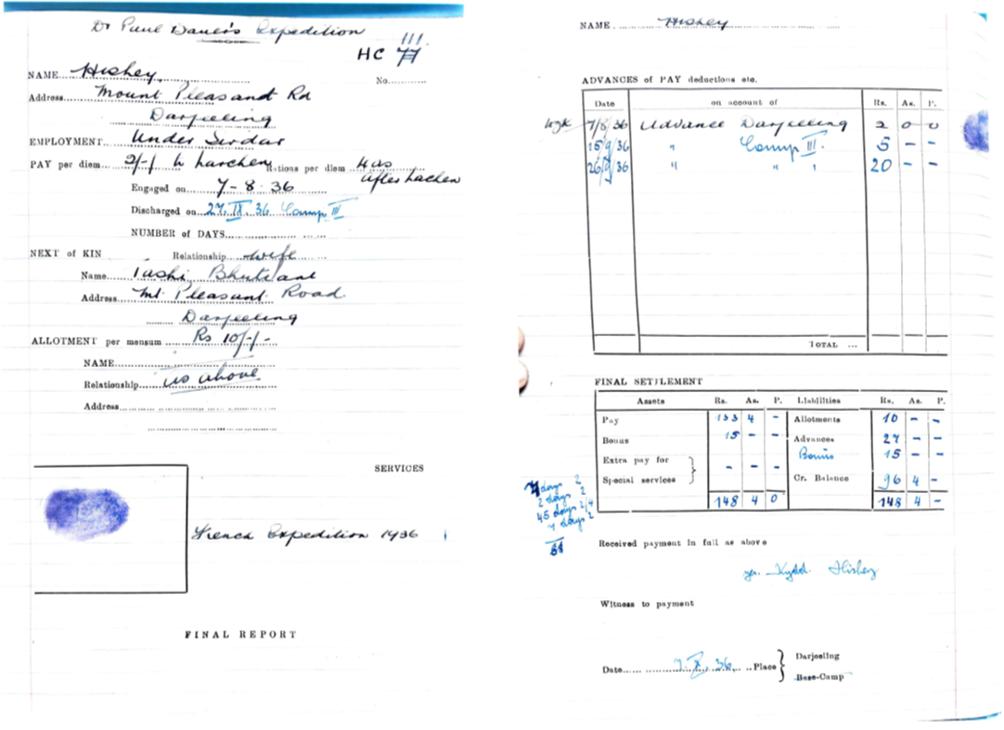

The most revealing of all these are documents on expedition finances. Such material ranges from broad statements on income and expenditure to the daily bookkeeping of the expedition. This material contains the fingerprints of the porter, both figuratively and literally. A file titled Brochüre contains details of the porters recruited in Darjeeling with their personal information, such as their addresses, next of kin and fingerprints, the details of their payment depending on which camp the particular porter went up to and at the end a remark by the European climber, his sahib, commenting on his performance on the mountain, which would determine his employment on future expeditions.[5] The pages of this register account for only a handful of the porters, including the cook and the sirdar (Trägerobmann – porters’ foreman) and suggest that these individuals were personally connected to each climber, as it was the practice to have a personal servant or orderly serving each individual climber during the course of the expedition. Such sources provide the possibility to trace payments down to the individual porters and even an opportunity to reconstruct personal histories. Within the various files are correspondences from individual porters themselves. These are addressed to the German climbers like Bauer, requesting references that would help them gain employment on future expeditions.[6] These rare correspondences raise the question of the literacy of the porters and the context in which they were able to write or have somebody write on their behalf.

The documents in the Archivalien der Expeditionsgesellschaften highlight the uniqueness of the expedition labour. They speak of an atypical workforce with tangents that show linkages to the military labour market, the remittance economy and household strategies, as well as identifiable individuals with some level of literacy. Recovering “hidden transcripts” – concealed strategies of resistance or negotiation embedded in the public interactions between groups in unequal positions of power – was an accessible approach formulated by James Scott in order to trace the lives of subordinated groups that do not leave behind much evidence of their own experiences (Scott 1990). A careful gleaning of this holding brings to light materials that can help write non-elite histories, to follow personal trajectories or the history of a group of people without being limited to searching for “hidden transcripts”.

This holding of the DAV on the expeditions to the Himalayas provides the details connected with labouring individuals that can be linked to materials from other archives to perhaps write a history of the lives of the Himalayan expedition labour.

Abbreviations

DAV — Deutscher Alpenverein (German Alpine Club)

DHS — Deutsche Himalaja-Stiftung (German Himalaya Foundation)

ÖAV — Österreichischer Alpenverein (Austrian Alpine Club)

DuÖAV — Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein (German and Austrian Alpine Club)

IHE — Die Internationale Himalaya-Expedition (The International Himalaya Expedition)

DRfL — Deutscher Reichsbund für Leibesübungen (German National Federation for Physical Exercise)

Endnotes

[1] https://www.alpenverein.de/geschichte/

[2]The archive of the DAV also holds a large collection of primary material from the Schlagintweit brothers.

[3]“German Expedition to Nanga Parbat”, Times [London, England] 2 Feb. 1938: pp. 10. The Times Digital Archive.

[4]This post is based on the research conducted between August to November 2019. A new online database will be updated in March 2020.

[5]DAV EXP 2 SG/206/0

[6]DAV EXP 2 SG/197, 198, 199, 200/0

Bibliography

Bauer, Paul (ed.), Himalayan Quest: The German Expeditions to Siniolchum and Nanga Parbat. London: Nicholson and Watson Ltd., 1938.

Bechtold, Fritz, Nanga Parbat Adventure: A Himalayan Expedition. 1st ed. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company Inc., 1936.

Höbusch, Harald, “Narrating Nanga Parbat: German Himalaya Expeditions and the Fictional (Re)Construction of National Identity”. Sporting Traditions 20, 1 (2003): pp. 17–42.

——–, “Germany’s ‘Mountain of Destiny’: Nanga Parbat and National Self-Representation”. The International Journal of the History of Sport 19, 4 (2002): pp. 137–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/714001794.

Holt, Lee Wallace, “Mountains, Mountaineering and Modernity: A Cultural History of German and Austrian Mountaineering, 1900–1945”. Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, Germanic Studies, 2008. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/3901.

Mason, Kenneth, Abode of Snow. A History of Himalayan Exploration and Mountaineering [with plates and maps]. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1955.

Mierau, Peter, Die Deutsche Himalaja-Stiftung Von 1936 Bis 1998: Ihre Geschichte Und Ihre Expeditionen. Dokumente des Alpinismus Bd. 2. Munich: Bergverlag Rother, 1999.

Scott, James C., Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990.

Nokmedemla Lemtur, CeMIS, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029