By Nokmedemla Lemtur

Published in 2025

DOI 10.25360/01–2025-00047

Photo: The Alpine Museum and the DAV Archive. Source: Photograph taken by the author, Munich, January 2020.

Table of Contents

Introduction | German Expeditionary Practices in the Himalayas (19th – 20th Century) | Expeditions as Sites of Cultural Production | Holdings of the DAV Archive | Endnotes | References

Introduction

The Deutscher Alpenverein (DAV), or the German Alpine Club, is one of the oldest and most significant mountaineering organizations in the world, tracing its origins to 1869. Its founding members had originally broken away from the Österreichischer Alpenverein (ÖAV), marking the beginning of an independent German mountaineering organization. In 1873, the DAV and ÖAV unified, forming the Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein (DÖAV), a collaborative effort that combined their resources and influence. However, this union came to an end in 1933, when the DÖAV split back into separate entities.

Initially founded to promote alpine exploration and study, the DAV grew to become a pivotal institution in the history of German alpinism and its cultural, scientific, and imperial ambitions. The archival legacy of the DAV, housed in Munich, provides a window into its rich history and entangled connections with other regions, including South Asia. This article explores the history of the DAV, the structure and content of its archives, and how these holdings shed light on significant Indo-German interactions.

The DAV was established in an era of burgeoning European interest in nature, exploration, and the scientific study of landscapes. Over the decades, it expanded its scope beyond mere alpinism, serving as a platform for cultural and scientific exchanges that mirrored Germany’s broader geo-political ambitions. By the early twentieth century, the club had become a central hub for moun-taineering-related documentation, facilitating the systematic collec-tion of expedition records, person-al papers, and artistic represen-tations of the alpine world and beyond.[i]

The DAV archives were institutionalized to preserve these materials, initially focusing on the Alps before expanding to include international expeditions, such as those in the Himalayas. The archive hosts an extensive collection, reflecting the multifaceted history of the club and its global endeavours.

German Expeditionary Practices in the Himalayas (19th – 20th Century)

The Schlagintweit brothers—Hermann, Robert, and Adolph—stand out as among the earliest German scientists to explore the Himalayas and Karakoram regions, then largely uncharted by Europeans. Their expedition (1854–1857) was inspired by Alexander von Humboldt’s vision of universal scientific inquiry and supported by the British East India Company and Prussian King Frederick William IV. However, this dual patronage created tensions, as the brothers navigated competing political, economic, and scientific priorities.

While the Schlagintweits sought to emulate Humboldt’s comprehensive approach by mapping both natural and cultural landscapes, their British sponsors prioritized economic intelligence and territorial knowledge. This divergence in goals, compounded by the uneven understanding of Asia in Britain and continental Europe, led to polarized evaluations of the expedition. Critics either lauded the Schlagintweits as pioneering explorers or dismissed their efforts entirely (Brescius 2015).

The Schlagintweit expedition’s outputs were remarkable for their scope, including vast inventories of geographical, topographic, and meteorological data alongside artistic and scientific representations. Among their significant contributions are the watercolours and drawings preserved in the archive of the Deutscher Alpenverein, which document landscapes, flora, and cultural sites across the regions they traversed. These artworks reflect not only the expedition’s scientific rigor but also the cultural perspectives and aesthetic sensibilities of the era.

In the twentieth century, the interwar years marked a significant expansion of German alpinism beyond the Alps, driven by shifting cultural attitudes toward mountains and mountaineering. Once seen as sites of recuperative leisure, mountains became arenas for asserting ideologies of masculinity and nationalistic pride, often with racial undertones (Mierau 2006; Keller 2016). Within this context, the Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein (DÖAV) emerged as a key institution in redefining mountaineering as a way of life, shaping German alpinists‘ ambitions to conquer ever-higher peaks.

A turning point came with the German-Soviet Alai-Pamir expedition of 1928, which culminated in the ascent of Pik Kaufmann (later renamed Pik Lenin), setting an altitude record for the time. This success fuelled the German alpinists’ aspirations to tackle the Himalayas. Between 1929 and 1939, German expeditions targeted Kangchenjunga in the Eastern Himalayas and Nanga Parbat in the west. These early attempts, beginning with Kangchenjunga expeditions in 1929, 1930, and 1931, were followed by a shift in focus to Nanga Parbat in 1932 and 1934.

Parallel to these developments, the political climate in Germany catalysed structural changes in mountaineering organizations. In 1933, the DÖAV was restructured and renamed the Deutsche Alpenverein(DAV). Recognizing the ideological and propagandistic value of mountaineering, the state intensified its involvement, leading to the creation of the Deutsche Himalaja Stiftung (DHS, German Himalaya Foundation) in 1936 (Mierau 1999). Under the leadership of Paul Bauer, the DHS provided funding, expertise, and logistical support for expeditions to the Himalayas. A series of climbs—1936, 1937, 1938, and 1939—attempted to scale Himalayan peaks, solidifying Germany’s presence in the region.

While these expeditions were undertaken under the banner of German nationalism, the climbers‘ experiences were shaped not solely by national ideologies but also by personal and regional identities. Many German alpinists, particularly those hailing from southern regions such as Swabia or Bavaria, drew on specific, regionally rooted memories to connect with the unfamiliar Himalayan landscapes (Neuhaus 2012, 190). These climbers often evoked imagery of the Alps as they sought to make sense of and relate to the strange and awe-inspiring environments they encountered. This interplay of national and regional identity highlights the complex motivations driving these expeditions, blending ideological narratives with deeply personal attempts to situate oneself within an unfamiliar world (ibid.).

The materials from these expeditions—ranging from photographs and correspondence to technical equipment—are preserved in the DAV archive. These records provide a rich resource for understanding not only the organization and outcomes of the climbs but also the cultural frameworks and personal narratives that underpinned these endeavours. After World War II, the DHS continued organizing expeditions until its dissolution in 1998. Another significant institution, the Herrligkoffer Stiftung (Deutsches Institut für Auslandsforschung, DIAF), supported several expedition to the Himalayas.[ii] Founded in 1952 by Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, this organization supported numerous post-war mountaineering ventures, ensuring the continuation of Germany’s alpine ambitions on an international scale (Herrligkoffer-Stiftung).

Expeditions as Sites of Cultural Production

The journeying of individuals into South Asia from the mid-19th century, which combined elements of exploration and mountaineering, encompasses a wide array of cultural, technological, and narrative dimensions. This multifaceted nature of such expeditions results in a rich variety of material, highlighting the interplay of adventure, media production, and cultural interactions. The holdings of the DAV illustrate these dynamics, positioning expeditions as key sites of cultural production.

Drawing on Martin Thomas’s framework (Thomas 2015), four defining traits of these ventures emerge. First, expeditions are characterized by the archetypal struggle of man versus nature. They test human limits, blending physical endurance with the ethos of extreme sports. Second, technology plays a pivotal role. Expeditions rely on advanced tools and instruments for navigation, survival, and documentation. These technological aids not only facilitate the journey but also frame the interaction between explorers and the less technologically advanced cultures they encountered. Scientific instruments and cameras, for instance, shaped how these encounters were recorded and interpreted. Third, expeditions function as “machines for producing discourse” (Thomas 2015, 16). They generate narratives that feed into the broader corpus of exploration literature. Visual objects—such as photographs, paintings, and postcards—serve as visual texts that reinforce or challenge dominant narratives of the time, influencing both academic and popular perceptions of the regions explored. Finally, media production emerges as a central purpose of expeditions. Documentation through photographs, films, and publications transcends the immediate goals of exploration, contributing to a broader media ecosystem. These materials not only commemorate the expeditions but also engage with larger audiences, creating a cultural footprint that extends far beyond the journeys themselves.

By combining these elements, expeditions into the Himalayas not only reflect the adventurous spirit of their participants but also serve as rich sites of cultural, technological, and narrative production, leaving a legacy in the form of diverse material and intellectual contributions.

Holdings of the DAV Archive

The DAV archive contains a vast range of materials categorized into thematic collections, each offering unique insights into the history of mountaineering, exploration, and cultural exchanges. While a significant portion of the archive focuses on the Alps, it also holds extensive materials from German Himalayan expeditions. These collections demonstrate the DAV’s involvement in international mountaineering and reveal the broader scope of its archival holdings, encompassing both Alpine and Himalayan exploration. The archive’s extensive catalogue, which includes details of these materials, can be accessed online at https://www.historisches-alpenarchiv.org/. Key holdings include:

1. Kunst- und Sachgutsammlung (Kunst/Sachgut) – Collection of Art and Material Goods

This collection features approximately 200 paintings, 2,200 prints, and a small selection of art objects that document the cultural fascination with mountains from the modern era onward. Highlights include travel watercolours and drawings by the Schlagintweit brothers, who traversed India in the mid-nineteenth century. The material collection also contains about 3,000 objects related to mountaineering equipment and alpinism since 1850.

2. Archivalien der Bundesgeschäftsstelle (BGS) und der Sektionen (SEK) – Records of the Federal Office and Sections

These records encompass correspondence, construction plans for alpine huts, and administrative files dating back to the DAV’s founding in 1869.

3. Historische Dokumente zur Alpingeschichte – Historical Documents on Alpine History

This collection includes hut and summit books, letters, prints, and newspaper clippings, offering a granular view of mountaineering history and firsthand experiences of climbers.

4. Archivalien von Expeditionsgesellschaften (EXP) - Records of Expedition Organizations

The archival material from expedition organizations, such as the DHS and the DIAF, spans the 1920s to 1990s. These holdings include expedition files, photographs, films, and sound recordings that document Germany’s Himalayan endeavours.[iii]

5. Nachlässe (NAS) – Personal papers

Personal papers of prominent alpinists and expedition organizers provide biographical and historical insights, enriching the understanding of individual contributions to the DAV’s legacy.[iv]

6. Fotografien und Postkarten (FOP) – Photographs and Postcards

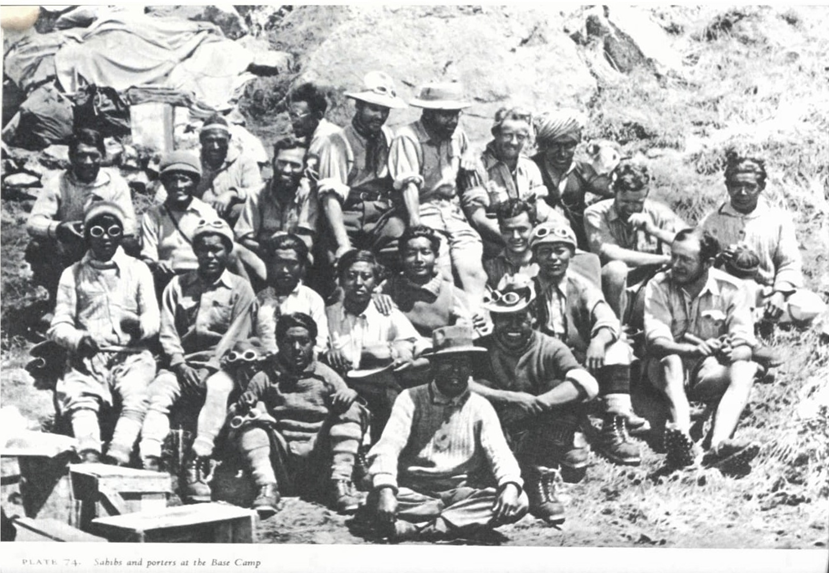

With over 25,000 items, this collection offers a visual history of alpinism, from thematic albums to rare glass plates. The photographs reveal not just landscapes but also cultural encounters and expeditionary practices.

7. Werbemittel – Advertising Materials

Posters, stamps, and other promotional materials with alpine motifs reflect the DAV’s role in popularizing mountaineering and fostering a national identity tied to the Alps.

8. Dokumentationen (DOK) – Documentations

This collection focuses on mountaineering missions abroad, capturing the global reach of German alpinism.

The DAV archive serves as a vital resource for understanding the history of German alpinism and its entanglements with other regions, particularly the Himalayas. Its extensive holdings offer insights into the cultural, scientific, and geopolitical dimensions of mountaineering, revealing how expeditions transcend physical journeys to become sites of cultural production and historical memory. By engaging with these materials, researchers can uncover rich perspectives on Indo-German history, exploring the layered narratives of exploration, technology, and cross-cultural exchange that emerge from the interactions between German climbers and the Himalayan region.

Endnotes

[i] For a detailed history on the Archive of the DAV: https://www.alpenverein.de/museum/sammlungen/archiv/archivgeschichte.

[ii] For complete list of mountaineering expeditions, see Lemtur (2021).

[iii] See Lemtur (2020).

[iv] See DAV MIDA Datenbank for list of persons: https://www.projektmida.de/datenbank/#/document/18868.

References

Brescius, Moritz von, Frederike Kaiser, and Susanne Kleidt (eds.), Über den Himalaya: die Expedition der Brüder Schlagintweit nach Indien und Zentralasien 1854 bis 1858. Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2015.

Göttner, Adolf, Himalayan Quest: The German Expiditions to Siniolchu and Nanga Parbat, ed. Paul Bauer, trans. E. G. Hall. London: Nichilson and Watson Ltd., 1938.

Herrligkoffer-Stiftung, “Stiftungsgeschichte”. https://www.herrligkoffer-stiftung.de/index.php/stiftung/stiftung-geschichte.

Keller, Tait, Apostles of the Alps: Mountaineering and Nation Building in Germany and Austria, 1860–1939. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Lemtur, Nokmedemla, “Locating Himalayan Porters in the Archivalien Der Expeditionsgesellschaften of the German Alpine Club (1929–1939)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2020). https://doi.org/10.25360/01–2022-00026.

——–, “Quellen zu deutschen Himalayaexpeditionen (1929–1989) im Archiv des Deutschen Alpenvereins (DAV), München.“ MIDA Thematische Ressource (2021). https://doi.org/10.25360/01–2022-00047.

Mierau, Peter, Die Deutsche Himalaja-Stiftung von 1936 bis 1998: Ihre Geschichte und ihre Expeditonen. Dokumente des Alpinismus Bd. 2. München: Bergverlag Rother, 1999.

——–, Nationalsozialistische Expeditionspolitik: Deutsche Asien-Expedition 1933–1945. Münchner Beiträge zur Geschichtswissenschaft 1. München: Utz, 2006.

Neuhaus, Tom, Tibet in the Western Imagination. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Thomas, Martin, Expedition into Empire: Exploratory Journeys and the Making of the Modern World. Routledge Studies in Cultural History 31. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Nokmedemla Lemtur, Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau, Nico Putz

Layout: Jannes Thode

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029