By Vandana Joshi

Published in 2019

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00023

Image: The main building of the International Tracing Service (ITS) in Bad Arolsen built in 1952. Copyright: International Tracing Service (ITS), photo: Andreas Greiner-Napp”

Table of Contents

The International Tracing Services (ITS) as a unique archive | Origins | Mission | British-Indian Soldiers at the ITS | Memory and memorialisation, interment and exhumation | Hidden transcript | The domain of work and non-work | Bibliography

The International Tracing Services (ITS) as a unique archive

This post brings to attention the existence of an international archive in the heart of Europe, largely overlooked by South Asian researchers working on WWII, who routinely visit the India Office Library (British Library), the National Archives of India, The National Archives in Kew, UK, and other regional archives engaging with the history of the British Raj. The (ITS) holdings complement the aforementioned sources both quantitatively and qualitatively if one is writing the history of British-Indian soldiers and civilians. Its speciality lies in giving historians access to individual destinies of South Asian soldiers, who entered the registers of German officialdom as an enslaved mass, serving a specific purpose in captivity, and the civilians who endured in the vagaries of the Third Reich.

Origins

As early as 1943, the Allied Forces transformed their Department of International Affairs into a Tracing Bureau in London for tracing and registering missing persons. The location of the ITS moved from London to Versailles, on to Frankfurt am Main and finally to Bad-Arolsen in January 1946. Bad Arolsen, a small town in Hesse/Germany, was chosen because of its central location between the four occupation zones and because its infrastructure was still intact after WWII.

Mission

The ITS has a fourfold mission: documentation, research, information and commemoration. The initial mission in the immediate post-war years was humanitarian, aimed at helping the kin and the victims trace each other and helping survivors in their rehabilitation. Gradually, it developed into a storehouse for posterity. This involved the preservation and production of documents related to several types of Nazi Party organisations and their actions, as well as those related to victims of Nazism. An important part of this was the registration of the persecuted foreigners and Germans alike by German public institutions, social welfare agencies (Sozialamt) and companies from 1939–47. The ITS thus gathered large amounts of approximately 30 million documents from concentration camps, ghettos, prisons, labour camps, sanatoria, infirmaries, asylums and later DP camps. The documents were generated in the form of filled out questionnaires on death, birth, marriage, divorce, hospital stays, and sanatorium, asylum or DP camp admission cards. Other documents included labour cards, medical cards or health insurance cards. This led to the generation of profiles of persecuted individuals across nationalities and regions.

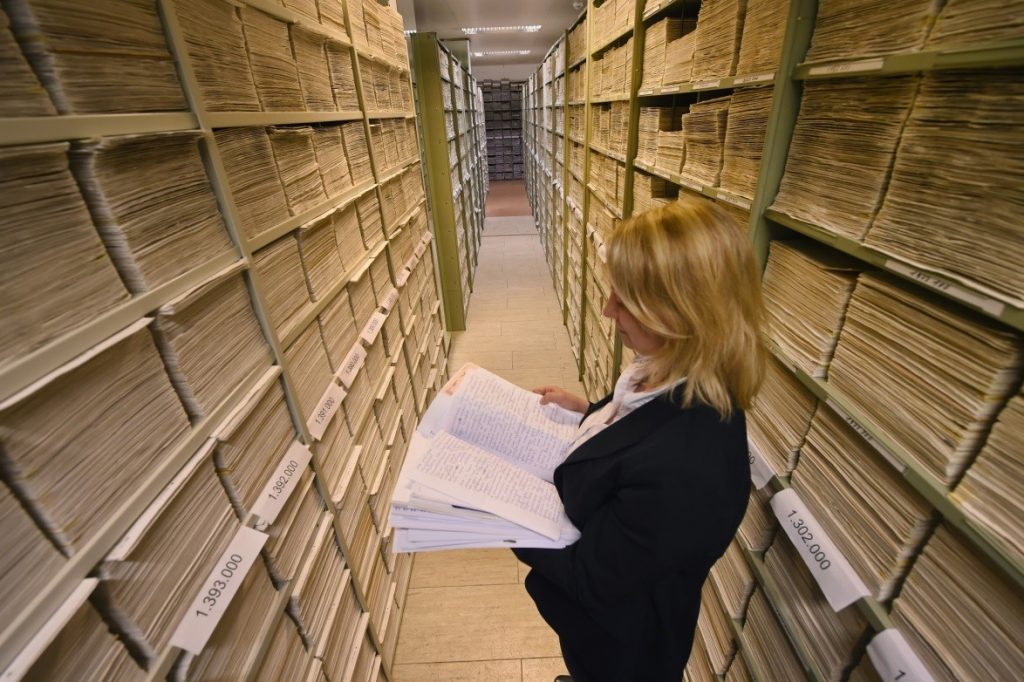

Copyright: International Tracing Service (ITS),

Photo: Uwe Zucchi

Since 2015, the archive has gradually been publishing an increasing number of its holdings on its Digital Collection Online platform, which provides small insights into the archive at https://digitalcollections.its-arolsen.org/.

Today, the archive helps scholars of the world in researching the ways in which one of the most well-organised and smoothly functioning states, namely Nazi Germany, operated in committing crimes against humanity. The ITS allows us to get underneath the skin of a criminal state and lays bare how the perpetrators’ mind operated during the war years, by preserving the records of the prerogative state. Simultaneously, it also generated its own records in the post-war era, which filled informational gaps, especially in the chaotic period from 1943–4, when the German landscape was filled with DPs and stateless people.

British-Indian Soldiers at the ITS

The first clue to the presence of British-Indian soldiers, the largest category in the ITS catalogue, is the Allied Order of December 6, 1945. It instructed all civilian authorities of Germany to conduct exhaustive searches for documents and information concerning military and civilian persons belonging to the United Kingdom since 1939 and to submit their findings immediately to their respective command of occupation forces. This British highway to the abode of British-Indian victims and survivors of the Third Reich led me to rich evidence for the history of institutional remembrance of British-Indian subjects in the heart of Germany. The very establishment of the ITS challenged Nazi knowledge production and reversed it by conducting targeted searches into what Nazis wanted to hide or destroy in the last years of war.

The available holdings deal with the identification, enumeration, registration and documentation of British-Indians as soldiers, civilians and displaced persons. An overwhelming proportion of these holdings consist of information about prisoners of war, dead or alive, from a host of Stalags (POW camps) Arbeitskommandos (labour camps), Lazarette (sick bays) and sanitaria or mental asylums. There are about 383 scanned images under Attribute IND, which consist of lists of soldiers in graves or cemeteries (with details such as the reason of death, date of birth and death, and grave location), labour camps and factories that housed them, payment registers, and so on. There is another set of 36 scanned images under Attribute Personalien IND, which deal with 5 civilians (among them students, housewives, DPs, seamen, civilians) and births and deaths of children born during the war years. As far as British Indian soldiers are concerned, the ITS collection is cloaked in icy silences when it comes to the spoken words of the persecuted. So, we practically have no ego documents or artefacts such as diaries, testimonies or letters from the survivors to give us a peek into their subjective world.

A striking feature of the lists is that they show the spatial spread and presence of the captives, despite their relatively small numbers, a presence, which was marked by their erasure/disappearance/death. There was no escape from the omnipresent threat of death during war years. This applied even more so to captives. If we barely take death records of the captives as an indicator, their geographical spread is exhaustive. Their corpses could be found in remote villages and towns such as Ansbach, Fuessen, Bad-Neustadt, Bad- Reichenhall, Bischoefsgruen, Berchtesgaden, Oelkofen, Garmisch, Regensburg, Oberroning, Westertimke, Herborn, Darmstadt, Bremervoerde, Nürnberg and Starnberg, Augsburg, Koenigsbrueck, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Wettering, Lauterhofen, Fulda, Giessen, Wiesbaden, Westertimke, Darmstadt and Sonthofen as isolated or cluster-graves.

Memory and memorialisation, interment and exhumation

Prisoners of war seldom speak out, deceased prisoners of war even less so. But the cultural politics of interment/knowledge/power, as it was played out over their mortal remains, left clues about the contestation over their imperial ownership. In the burial ‘rites’, if one may call them rites at all, it became gradually clear as to which empire lorded over whose corpse and whose corpse was disowned by both. The British and German empires locked horns once again in the post-war years amid the corpses of their captives on the battle field of memory and memorialisation, interment and exhumation. So, there were these corpses and there were those corpses. There were some whose presence was noted on a shred of paper stamped “grave registration”.

These could be the very ordinary prisoners of war, neither definitively on this nor on that side. Then there were some others that lay buried in military or civilian cemeteries with grave numbers and personal details recorded on the certificates. These were possibly the Indian Legion soldiers. And then there were those corpses that were exhumed by the ITS team, brought to a war cemetery in Berlin, or transported to a more appropriate location. There they were interred once again, this time with full state honours. Their martyrdom and memory was etched in stone for posterity. They secured a place in the cultural history of memorialisation as a reward for their loyalty to the British Empire till the bitter end.

In the Thompsonian sense, then, the ITS holdings enable historians to rescue British Indian soldiers, dead or alive, irrespective of their virtues and vices, from the condescension of posterity (Thompson, 1980: 12), as twice colonised peasants in uniforms, as culturally and socially exposed to a cosmopolitan environment behind the barbed wire, which taught them survival strategies that they knew little of when they left home on an uncertain journey.

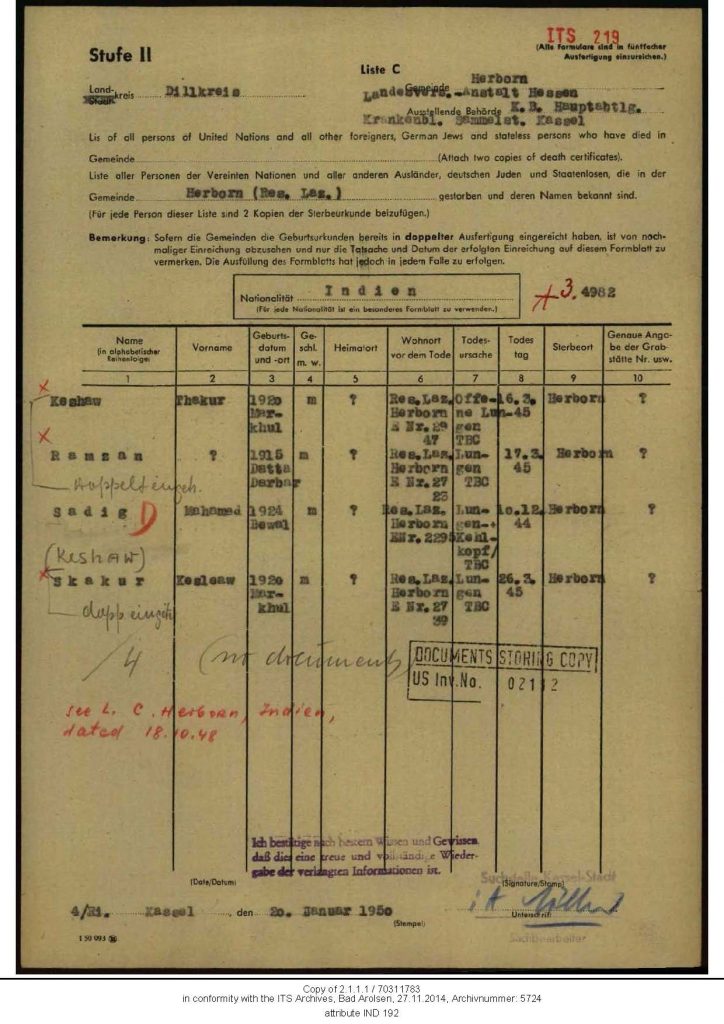

Although usually inherent to knowledge generation for posterity, some of the holdings nonetheless betray an element of compulsion ‘from above’, (this time from the “Allied”), to report the dead, surviving, or missing persons. The official reluctance on the part of the Germans to generate or furnish such documents can be traced in some instances. This is proven by the presence of grave certificates that were produced at a much later date. To give one example- on one instance the certification from a civil functionary reads at the end of a document: “I certify to the best of my knowledge and conscience that the required information given above is the correct and complete reproduction of available documents at hand”. The document is stamped for the year 1950, though the actual dates of deaths were much earlier (1944 and 1945). Thus, as can be seen in the image below, there was reluctance in reporting deaths as can be discerned from the fact that such sworn documents were furnished years later.

Copy of 2.1.1.1/70311783, in conformity with the ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen, Archivnummer: 5724, attribute IND 192. Image courtesy The ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen.

Hidden transcript

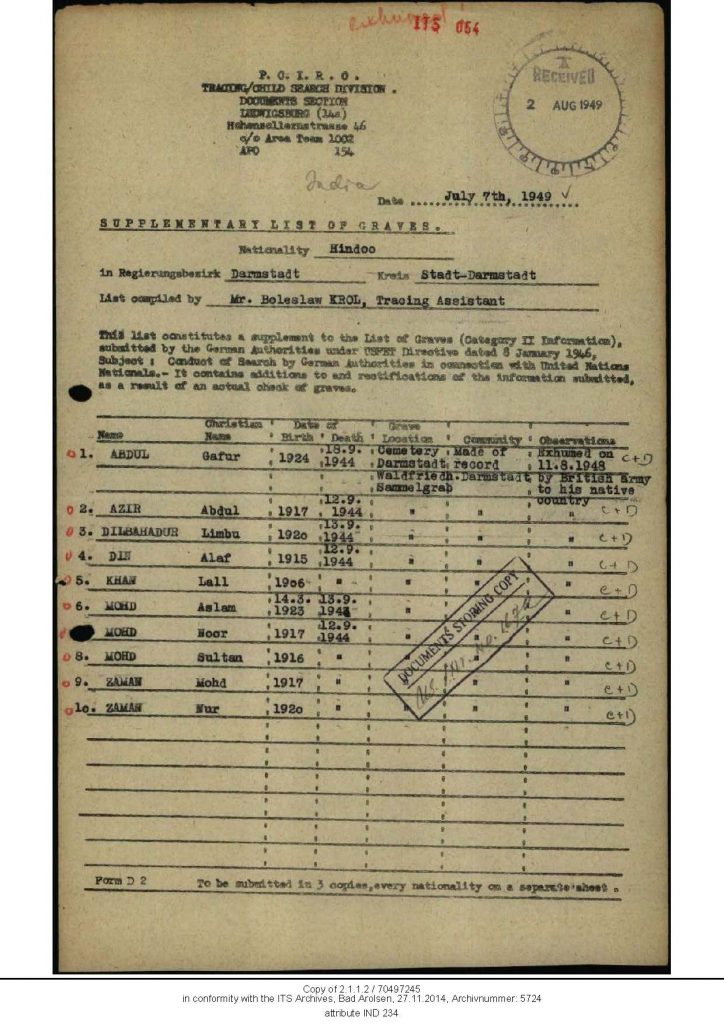

What was recorded and preserved willingly or unwillingly at the ITS, might fill any historian with a sense of void, the loss of spoken word, of non-verbal exchanges, of gesture and gaze. Nevertheless, if one goes with the sensibilities of anthropologists and everyday historians such as James Scott, Carlo Ginzberg and Alf Lüdtke, one might be able to find hidden transcripts (Scott:1990), the off-stage everyday life, and attempt to recreate it through the small clues and hints that oppressors’ records have left behind. The following example illustrates this: It is taken from the lists of deceased captives. Despite the significant geographical spread of captives’ graves, I found clues to omissions, wilful or otherwise. Some cases were reported as late as 1947, 1948 or even 1951. Columns such as place of birth and death and reason of death were either left blank or noted unknown in several forms. Renewed searches were conducted, which resulted in Supplementary Lists of Graves. Fresh sites were dug up by search teams, corpses were exhumed and their personal details added to registered deaths subsequently. One such Supplementary List of Graves reported a collective grave of 10 captives in July 1949. They had been dead since September. 1944. It turned out that 9 of them died in a single air raid and the one remaining succumbed to his abdominal membrane infection a week after the air raid.

Copy of 2.1.1.2/70497245 in conformity with the ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen, 27.11.2014, Archivnummer 5724, attribute IND 234. Image courtesy The ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen.

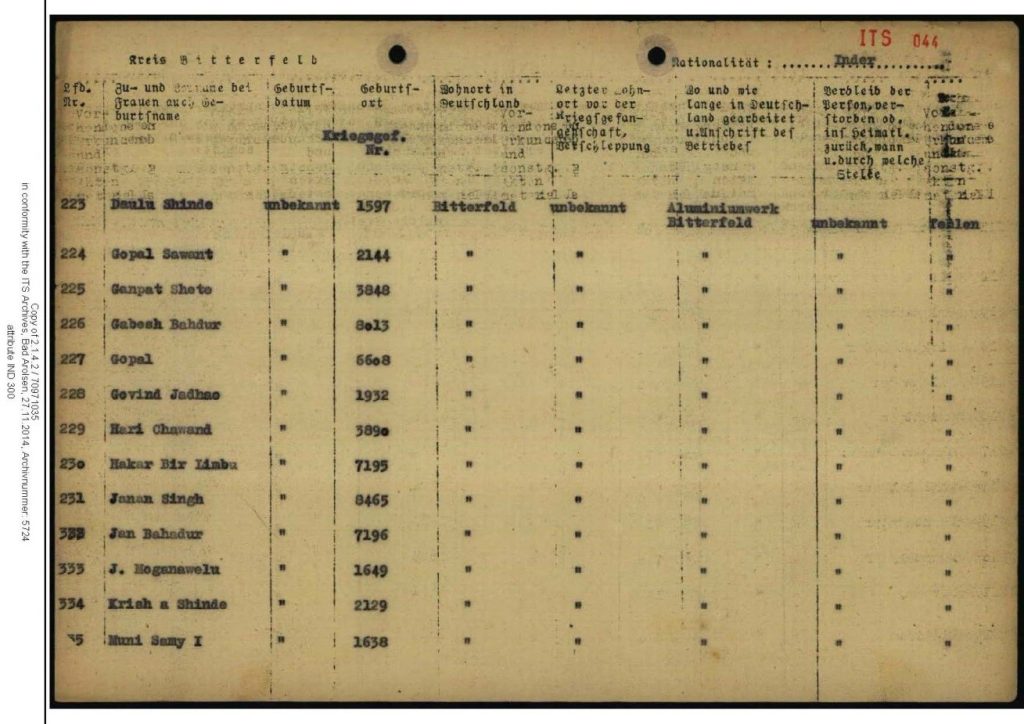

The other numerically rich, but spatially concentrated category of captives consists of forced labour around Saxony, Rheinland Palatinate and parts of Baden Wuerttemberg as shown in the image below.

Copy of 2.1.4.2/70971035, in conformity with the ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen, 27.11.2014, Archivnummer 5724, attribute IND 300. Image courtesy The ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen.

The domain of work and non-work

What did everyday life mean to a captive? What was the domain of his work and non-work? To get a sense of how the everyday forms of domination and subordination worked, we need to go to local sites inhabited by Indian captives to observe how Indian officers acted on the ground to convert captives for the cause of the Indian Legion and persuade them to join it. “The POWs were often ill treated. It became a custom to make the prisoner visit ‘the conversion camp’ at Lacanau where he was shown the advantages of a legionary’s life. Those who declined were pressurised by other means to comply” (Oesterheld 2015). Though such subjective narratives cannot be found at the ITS, I found some payment entries of the IG Farben, a German enterprise, which allow us a glimpse into what work might have meant to the captive. These registers show a schedule of 8 hours a day, 6 days a week until liberation in mid1945 for half a Reichsmark per day. Hackenholz, who worked on the history of IG Farben, suggests that even Russian captives received better wages than the Indian ones. Indian prisoners received between 20 to 60 % of a regular West European’s wage and the east European prisoner stood somewhere in between (Hackenholz: 2004).

All captives were indispensable labour for the war industry and their loss was detrimental to war effort. Not all captives could remain fit for work in the long run. In Annaburg there were 6 reported deaths due to lung infection, suicide, heart attack, abdominal diseases, and similar unnatural reasons. Elsewhere, deaths were caused by depression, schizophrenia, suicide, exhaustion, nervous break-down and mental illness in isolated locations.

Though the affective domain was all encompassing, its traces are more challenging to find. The ITS records are dominated by looming silences and erasure. I have relied on snippets from the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) reports, memoirs and judicial records to recreate the world of captivity, which have been published elsewhere (Joshi: 2015). Here I will cite just one illustrative example, namely the fortnightly reports of the SD on the mood and morale of the general public, compiled and published by Heinz Boberach (Boberach: 1984). The SD observers were state appointed ‘silent mass observers’, who constantly had their finger on the pulse of the ordinary people, including the captives. They recorded disloyalty, disgruntlement and grumblings among the population so that appropriate measures could be taken for the smooth functioning of the system. Unlike the quantitative approach of the ITS, this SD observation is full of vivid details on South Asian captives’ deportment, behaviour, and attitudes. These are the most colourful examples in which power holders revealed their attitudes, biases, hope and fears. The SD report filed on 20 March 1944, starts with the following observation:

The experience with Indian captives is as negative as with British POWs. They are unsuitable for industrial and professional use and can only be employed either in digging the earth (e.g. for air raid shelters) or as helpers in munitions firms. Their performance is so much below the lowest German average that the firms soon look for replacement. They categorically refuse to work and invoke the Geneva Convention. Even the request to their supervisors to exert an educational influence is dismissed with the remark that any punitive measures would be useless. If one confines them, they have the option of sleeping in arrest. Depriving them of food similarly brings them no great harm as they are abundantly supplied with Red Cross parcels and food packets from home. This passive attitude of the supervisors extends to the entire contingent. Half of the contingent just looks on while the other half digs the earth. Rather than keeping themselves warm by working, they prefer to freeze. They keep their hands perpetually in their trousers’ pockets and cover their heads with shawls in such a manner that only their eyes and noses are visible. Those who work pick just one-third of soil in their shovel of what an average worker would (Boberach 1984: 6424–5).

While the SD observations condemn Indian captives as shirkers and a financial liability on the Reich, the payment registers of Faserwerk Mühlanger, supplied to the ITS team tell another story. One payment list of 17 captives shows that they worked on a Sunday 11.7.43 (Payment list of Indian POWs, 2.1.4.2/71044351). The IG Farben lists show that one Kalyan Singh worked for 10 hours per day for 2 weeks and 10 hours per day for 9 days in the rest of the two weeks in February 1945. This made it 230 hours in 28 days for which he got paid only 34 RM. The average monthly payment for others was 22/23 RM. Another Karak Bahadur worked 10 hours per day, twice even 11 hours for the entire month of February 1945 and received 48 RMs for a total of 290 hours, one Dhan Bahadur worked for up to 12 hours, 5 days in week, 60 hours per week in the second week of January, earning 36 RMs for the month, for 245 hours of work. Why were they working so hard in the bitter cold of February 1945? Earning more would hardly have been an incentive as they were paid in coupons that were exchanged for food and forbidden exchange invited further punishments.

Silences and erasures notwithstanding, the ITS holdings have a unique purpose and value. They provide us with lists of British-Indian soldiers in large numbers, with names and identification details that might be difficult to find in other type of records generated by Nazi officialdom such as decrees, commands and instructions from the Foreign office. The same holds true for media accounts, which mostly reported the spectacular and newsworthy to create fear and alarm in order to ensure compliance, or propaganda material that was more of a projection rather than the reality of the camp universe. The ITS holdings cover an exhaustive range of details connected with identifiable individuals that historians and researchers can follow up by looking at complementary subjective documents and other instructive material in order to write a history of the everyday life of British-Indian prisoners in the Third Reich.

Bibliography

Boberach, Heinz, Meldungen aus dem Reich 1938–45. SD Berichte zu Inlandsfragen vom 27. Dezember-20 1943 bis April 1944. Band 16. Herrsching, 1984.

Hackenholz, Dirk, Die Elecktrochemischenwerke in Bitterfeld 1914–45: Ein Standort der IG Farben. Münster: Lit Verlag, 2004.

Joshi, Vandana, “Shreds from the Lives of South Asian Prisoners of War in Stammlagers, Arbeitskommandos, Lazaretts and Graves During World War II (1939–45)”. Südasienchronik 5 (2015): S. 144–168. https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/9148/145.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Oesterheld, Joachim, “The Last Chapter of the Indian Legion”. Südasienchronik 5 (2015): pp. S. 120–143. https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/9147/121.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Scott, James, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. Yale: Yale University Press, 1990.

Thompson, E.P., The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Pantheon Books, 1964.

Vandana Joshi, Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029