By Baijayanti Roy

Published in 2021

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00029

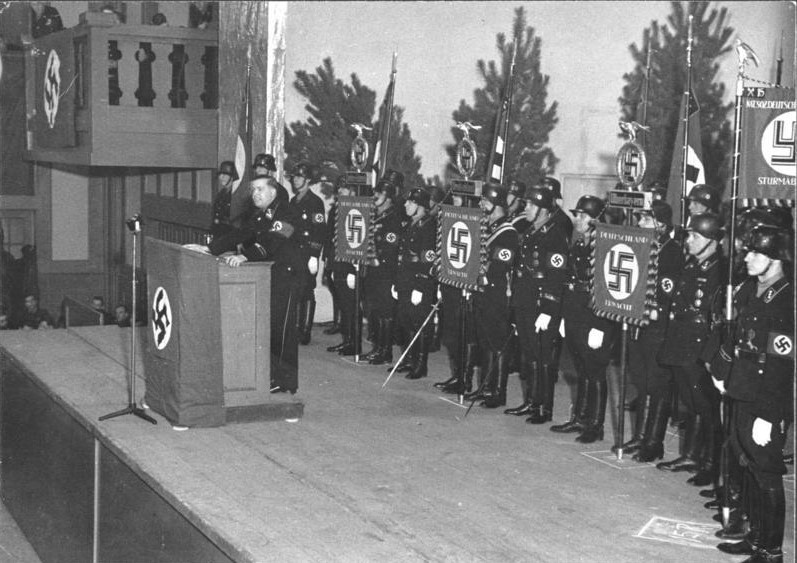

Figure 1: Walther Wüst giving a lecture with the topic: „The Führer’s book ‘Mein Kampf’ as a reflection of the Aryan worldview” at the Hackerkeller, Munich, Germany on the 1oth of March 1937.

Table of Contents

Background | India Institute 1928–1933 | India Institute 1933–1945 | Archival Sources | (Bundesarchiv) Federal Archives, Koblenz | State Archives of Bavaria (Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv or BayHstA) | Journal of the DA | Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin) | Federal Archives, Berlin-Lichterfelde | Thierfelder’s writings | Conclusion | Endnotes | Bibliography

Background

The India Institute (Indischer Ausschuß) came into existence in 1928 as a part of the Munich based Deutsche Akademie or “German Academy” (henceforth DA). The latter had been founded as a private cultural organisation in 1925 by a group of academics affiliated to the University of Munich. The aim was to disseminate German language and culture in the world. India Institute was the first of a number of committees within the Deutsche Akademie that were established for specific nations.

The India Institute was set up through the efforts of Taraknath Das, an Indian nationalist living in Europe and Karl Haushofer, professor of Geography at the University of Munich who was involved with the DA from the start. Haushofer had visited India in 1908–1909 and had developed a sympathetic interest towards the British colony (Spang, 2013: 336). The organisantional part of the India Institute was entrusted to the young journalist Franz Thierfelder. He was the General Secretary of DA from 1929–37 (Michels, 2005: 3).

After the First World War, Germany tried to compensate its lack of political clout in the international arena with “soft power,” exerted through supposedly non-political associations like the DA which officially engaged in the spread of German culture. In reality, the separation of political and cultural spheres was often only cosmetic (Scholten, 2000: 41–42). From its modest beginnings during the Weimar Republic, the DA rose to become the most important organisation representing Nazi cultural policy. It was banned by the occupying American forces in 1945. This also signified the end of the India Institute.

As part of the DA, the Institute also claimed to be a non-political organization with the sole aim of promoting cultural ties with India. This was to be done by providing stipends to Indian students and professionals to study and work in Germany, by inviting distinguished Indians to Munich, and by spreading German language and culture in India.

While there are several scholarly studies that critically examine DA’s past (Harvolk, 1990, Kathe, 2005 and Michels, 2005), the trajectory of the India Institute remains uncharted, except for a relatively short study (Framke, 2013: 66–79). My present research (as part of the DFG project “Indology in Nazi Germany”), indicates that from its very beginning, India Institute espoused the interests of the German state.

The “purely cultural” image of the DA and its affiliated institutes rendered them an aura of political innocuousness and credibility. Hence, propaganda undertaken by them was particularly effective. Their non-political façade also provided good cover for espionage. The NS regime increasingly took advantage of these conditions. In exchange, the DA received much needed financial assistance and esteem. Despite British surveillance, India Institute could carry on propaganda and espionage in India till the outbreak of the Second World War.

In the following sections, I first provide a brief overview of the Institute’s history till 1945, based on my own archival research as well as secondary sources, before discussing relevant archival sources on the subject.

India Institute 1928–1933

During the years of Weimar Republic, Germany’s approach towards India entailed projecting itself as a covert sympathiser of India’s strife towards economic development and political autonomy. Following this course, the India Institute collaborated with the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, which was a front for the scholarship program of the Foreign Ministry. The Institute and the Foundation jointly provided scholarships to Indians with the aim of attracting sympathy for Germany (Impekoven, 2013:20).

Germany, which had commercial interests in India, could not afford to antagonise the British colonial authorities since the latter controlled access to the Indian market and production (Barooah, 2018). Hence, India Institute’s policy was to encourage moderate Indian nationalists and honour Indian icons who were acceptable to the British colonial establishment. The Institute also realised that these elite Indians were likely to be the best conduits for propagating Germany’s views and interests in India.

A number of German Universities (Munich being the foremost), Technical Academies as well as commercial firms like Siemens and Allianz co-operated with the Institute in providing scholarships and traineeships to Indians. These firms had branches in India and sought to use the Institute to promote their commercial interests.

The Institute, in turn, needed academics with discursive knowledge of India for dealing with the country as well as to familiarize German opinion-making classes with India, in order to reinforce its own status as a mediator of Indo-German cultural relations. This demand was fulfilled by a number of scholars from various disciplines, including indologists.[i]

India Institute 1933–1945

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, the DA mobilized itself to conform to the new regime’s expectations, in the hope of getting necessary financial help. Transformations in the DA after 1933 included expelling the “politically and racially undesirable” members from its governing units. In 1934, Karl Haushofer was made President of both the DA as well as the India Institute. Haushofer was not a member of the Nazi party but his geopolitical theories enjoyed some respect in Nazi circles. He was expected to bring in funds from the regime without tarnishing DA’s apolitical image. Haushofer’s student and friend Rudolf Heß, now deputy to Hitler, was welcomed in the DA´s Executive Council (Michels, 2005:105–111).

One of the “tasks” that the India Institute took upon itself after 1933 was to defend the Nazi regime against indictments of rising racism towards Indians, reports of which appeared frequently in Indian press. The result of such negative publicity was a temporary decrease in the number of Indians applying to pursue academic studies or professional training in Germany. On behalf of the India Institute, Thierfelder and Das embarked on a counter propaganda which insisted that beneficiaries of the Institute were “safe” in Germany if they desisted from “political activities,” a euphemism for left-wing politics including radical anti-colonialism. Instead, stipend holders were to acquire “the best of German culture,” which stood for the National Socialist worldview.

Das left for the US in 1934, though he continued to be a corresponding member of the Institute. His wife Mary Keating Das financed a scholarship for medicine from 1936 and was made a life member. Another Indian spokesman for the Institute was the “Germanophil” Benoy Kumar Sarkar, a polymath and professor of Economics at the University of Calcutta. Sarkar had travelled extensively in Europe, in the course of which he had developed friendly relations with Karl Haushofer. Through him, the India institute arranged for Sarkar’s appointment as a guest professor at the Technical Academy in Munich in 1930–31. While Das did not approve of Nazi Germany’s rising anti-Semitism, Sarkar was willing to defend it. He saw in the “Third Reich” a rejuvenated Germany and an inspiration for India. Sarkar consistently promoted the interests of the Institute and Nazi Germany in India.

An aspect of the Institute was its partiality towards scholars and mystics associated with Hindu revivalist movements. A common goal shared by these disparate movements was to revitalize Hinduism by taking it back to its purportedly glorious Vedic Aryan roots. After 1933, the India Institute offered propaganda platforms and scholarships to individuals associated with such Hindu revivalists. The intention was to use these “agents” to spread Nazi propaganda among Hindus through analogies based on Aryanism.

The Institute was particularly drawn to a Hindu reform movement called the Arya Samaj or the “Society of Aryans” which imagined India as a Hindu “Aryan” nation where other religious groups had no rightful place. The “Aryan content,” along with the majoritarian and authoritarian character of this movement, made it compatible with some racial and disciplinarian aspects of Nazism, including a eugenicist dimension (Gould, 2004: 157–158). Though apparently non-political, Arya Samaj also had an undercurrent of anti-colonial activism (Fischer-Tine, 2013).

The India Institute collaborated with the department of “Aryan Studies” at the University of Munich, offering scholarships to Indians to study at the University and teach Indian languages. Candidates associated with the Arya Samaj were unofficially given preference. The Indologist Walther Wüst, member of the India Institute and professor of “Aryan Studies” at the University of Munich, arranged to set up this position. Wüst was a member of both the Nazi party and the SS. After 1933, Wüst‚s scholarship often tried to connect “Aryan India” with Nazi Germany (Junginger, 2008).

Notably, the India Institute also encouraged “racial anthropology” based on Aryan discourse. In collaboration with other German institutions, it invited Indian “race scientists” as academic guests and students in Germany.

By 1936, despite Haushofer’s efforts, DA’s economic position became precarious. In order to attract funds, DA increasingly turned towards the government, which on its part started to use it more intensively. The amount of influence that the regime was to exercise in the DA became a contentious issue, leading to the resignation of both Thierfelder and Haushofer. Thierfelder left the DA but continued to conduct propaganda for Nazi Germany. Haushofer remained in DA’s executive council and succeeded in making his protégé Walther Wüst the President of the Institute in 1937 (Michels, 2005: 102–119). In the same year, Wüst also became the President of the SS-Ahnenerbe, Heinrich Himmler’s organization for pseudo-scientific “ancestral research.” Wüst tried to integrate India Institute into the network of SS and the Ahnenerbe in different ways.

In June 1938, the DA was placed under the Foreign Ministry’s “cultural political section” which, along with other functions, also conducted anti-British and pro-Nazi propaganda in India. Thus, both DA and the India Institute became fully integrated in Nazi Germany’s external politics (Kathe, 2005:75). The Nazification of DA was complete when Ludwig Siebert, a committed National Socialist and chief minister of Bavaria, became its president in 1939.

With the start of the war, “cultural ties” with India became impossible to maintain. The India Institute now openly participated in the propagandistic venture to present Nazi Germany as a champion of India’s independence by promoting books that were strongly anti-British in tone. After Siebert’s death in November 1942, Walther Wüst became the working head of DA in addition to being the head of the India Institute. He continued in this role till Arthur Seyß-Inquart, “Reichsminister” and Commissioner for occupied Holland, became the President of DA on 10th February, 1944, underscoring the DA’s prestigious position.

The concurrence of interests of the DA/India Institute and the Nazi regime was best reflected in the profiles and activities of the three lectors who were sent to India by DA to teach German. Apart from this official task, they were semi-officially required to engage in “cultural political activities” which denoted espionage and propaganda for the NS regime. The first of these lectors was Dr. Heinz Nitzschke, who had finished his doctoral studies at the Leipzig Universität, arrived in Calcutta in November 1933. Nitzschke was a member of the Nazi party, who lost little time in promoting the “Third Reich” in India. He was succeeded by Horst Pohle, a member of the Nazi party as well as the Nazi Teachers’ Association (NSLB), in 1934. Pohle´s journey to India was paid by German Foreign Ministry. The third lector was Alfred Würfel, trained as a Volksschule teacher who specialized in English, also a member of the NSLB, who arrived in Banaras in October 1935. Both the lectors were interned by the British authorities as “enemy aliens” after the Second World War started.

Archival Sources

Important archival materials on the India Institute are at the India Office Records, London, the National Archives of India, New Delhi and the West Bengal State Archives, Kolkata. The archives in Germany that have materials on the India Institute are: (i) Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv), Koblenz (ii) State Archive of Bavaria (Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, henceforth BayHstA) Munich (iii) The Leibniz-Institute of Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin), Munich, and (iv) (Bundesarchiv) Federal Archives, Berlin-Lichterfelde. Summaries of the relevant holdings in each of these archives are provided below.

(Bundesarchiv) Federal Archives, Koblenz

The Nachlass or papers of Karl Hauhofer (signature NL 1122) provide substantial information about the India Institute. Glimpses of the Institute‚s beginning can be found in Haushofer’s correspondence with Taraknath Das (NL1122/6). The correspondence, which started in July, 1925, shows that an underlying anti-British sentiment shared by the two formed the backdrop to the foundation of India Institute. The idea of such an Institute came from Das. Haushofer managed to convince the DA of its necessity. The letters show that India Institute started actual work from 1929.

Haushofer’s interest in India’s anti-colonial politics is recorded through his exchange with the radical activist Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, who then lived in Berlin (NL1122/5). Chattopadhyaya and Das were part of the Berlin-based India Independence Committee formed during the First World War (Liebau, 2019).[ii] Haushofer’s correspondence with Benoy Kumar Sarkar (NL 1122/28) provides an idea of the latter’s engagements for Germany before and after 1933.

The correspondence of Das and Thierfelder, preserved under the signature NL1122/6, bear testimony to their untiring efforts to induce the government of Bavaria, different academic and technical institutions, as well as industrial firms in Germany to assist the India Institute.

State Archives of Bavaria (Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv or BayHstA)

Primary materials preserved at the BayHstA in Munich (under the signatures MK 40443–40445) are indispensable for any study on the India Institute. Among the holdings here are lists of members of the India Institute and “corresponding honorary members” from India. The latter included Indian luminaries like the Nobel Laureates C.V. Raman and Rabindra Nath Tagore, who were honoured by the Institute as they toured Germany (MK 40444). The annual reports of the Institute accessible under the signatures MK40443-40444, provide details of the institute’s activities from 1929–1933.

Under the signature MK 40443, there is a record of an interesting lecture series organized by the India Institute and held at the University of Munich in the winter of 1932/33. Some of the lectures had political undertones which would assume greater significance in the Third Reich. For instance, Karl Haushofer spoke on the geopolitical significance of India. Similarly, Indologist Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, Professor at the University of Tübingen and a member of the India Institute who would go on to offer different services to the NS regime, spoke on Yoga as a part of the glorious spiritual history of Nordic Indo-Aryans, whom he projected as ancestors of modern Germans.

Journal of the DA

An invaluable source for the history of the India Institute is the journal of the DA, titled Mitteilungen or “Announcements” available at BayHstA (signature Z236). Among the significant entries is one from the first issue of March 1936, documenting the expulsion of two “Jewish Indologists,” Lucian Scherman and Otto Strauß from the Executive Committee of the India Institute (Mitteilungen: 165). This announcement contradicts Thierfelder’s post war claim that he managed to avoid implementing the notorious “Aryan paragraph” of 1933 in the DA (Scholten, 2000:100).

The journal records instances of the India Institute’s attempts to defend the international reputation of Nazi Germany. The third issue from November 1934 mentions, for example, that M.S.Khanna, an erstwhile stipend holder of the Institute, published a “misleading and partially made up account” of the harassments faced by Indian students in Germany. The Institute responded by mobilizing its associates and erstwhile beneficiaries in India to write articles countering this report (Mitteilungen: 398).

Mitteilungen regularly reported on Benoy Kumar Sarkar’s attempts to promote aspects of Nazi Germany through various publications as well as through a “Bengali Germany Knowledge Society” that he had established in Calcutta in 1932. From these reports it transpires that erstwhile stipend-holders of the India Institute were involved in this Society as organizers and speakers. After 1933, the Society arranged lectures on subjects associated with National Socialism – like national community (Volksgemeinschaft), militarisation, and genetic selection. The Institute recognized Sarkar’s contribution by electing him as one of its honorary life members in 1933 (Mitteilungen: October 1933: 392).

The connections between the India Institute and Hindu revivalism as well as racial anthropology can also be traced from different issues of Mitteilungen. For example, a lecture delivered by a guest of India Institute, Professor B.S. Guha, titled “The racial foundation of the Indo-Aryans and racial miscegenation in India” was published in 1935 (Second Issue July 1935: 488–496).

From 1937, the journal changed its name to Deutsche Kultur im Leben der Völker or DKLV (“German culture in the lives of the people”). Henceforth it routinely published Walther Wüst’s writings glorifying Germany’s “Aryan past” as well as reviews of books championing Indian anti-colonial struggle. A notable example is Wüst’s sympathetic review of the German translation of the polemical book, “The Indian war of independence” written anonymously by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, the anti-colonial activist turned champion of politicized Hinduism (DKLV, December 1941: 122).

Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin)

The archive of the Leibniz Institute of Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin), in Munich has protocols of some of the meetings of India Institute from 1934–1938 (Signature: MA 1190 and MA241). The protocol of a meeting held on 23rd October, 1934 for example, reveals that the India Institute blamed Mussolini and his government for instigating Indian students against Germany (MA1190). Another meeting held on 1st February, 1937 (MA 241) records the relief expressed by the Executive committee about the departure from Europe of “certain people” who fomented disturbance among Indian students in Berlin and Munich (alluding to the nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose who instigated Indian students to protest against racism during his visit in 1934). The protocol of the meeting of the Institute on 27th October, 1938 (MA1190) indicates that Benoy Sarkar postponed accepting the Institute’s invitation to visit Germany because the “negative propaganda” about Nazi Germany actually scared him.

Federal Archives, Berlin-Lichterfelde

A holding at Federal Archives, Berlin (Signature R51) provides insights into the “cultural political activities” undertaken by Horst Pohle and Alfred Würfel, the two lectors sent to India. The holding contains the correspondence of the two lectors with various functionaries of the DA. “Reports” sent in 1938–1939 were sometimes part of this correspondence though more “sensitive” information were sent through diplomatic channels of the German Consulate in Calcutta, as the letters claim.

Würfel’s “activities” (signature R51\10128) included the distribution of publications promoting the “New Germany” among his students, some of whom were professors at the Banaras Hindu University. Pohle’s letters (signature R51\144) are more explicit. They reveal that he kept a tab on the European Jews who sought refuge in Calcutta after fleeing the Nazis. He also reported on India’s political situation and noted the country’s responses to happenings in Germany. As a Nazi party member, Pohle kept in touch with the Nazi external cell (Auslandsorganisation) based in Bombay. Both the lectors were aware of being spied on by British surveillance, as is clear from their correspondence.

Thierfelder’s writings

A brochure titled “India Institute of the Deutsche Akademie,” composed by Thierfelder and published in 1937, provides a detailed “first-hand account” of the Institute. The brochure systematically names the Institute’s office bearers, different kinds of members, stipend holders and guests. India Institute’s political orientation is manifest in the statement that “Foreign anti-German propagandists under the guise of students are not welcome” (Thierfelder, 1937: 7–8). The brochure also provides visual records of the Institute’s past in the form of a number of photographs.

In 1959, Thierfelder published another article on the India Institute commemorating thirty years of its existence. In this essay, he presented the Institute as a politically neutral organization which kept its distance from the Indian anti-colonial movement as well as Nazi politics (Thierfelder 1959: 92–102). This article is a perfect example of a retrospectively manipulated account of the past, as this brief review of the Institute’s history demonstrates.

Conclusion

The sources from different German archives make it clear that the India Institute, much like its parent organisation, the DA, identified with the concerns of successive German regimes. After 1933, the Institute became increasingly involved in a cultural policy that was compatible with the interests of the NS regime, which granted it financial security and prestige in return. Following the outbreak of the Second World War, the India Institute openly and completely identified with Nazi Germany.

Endnotes

[i] Apart from those mentioned in this article, the indologists at the Institute also included Helmuth von Glasenapp and Wilhelm Geiger.

[ii] See also Heike Liebau’s entry on the India Independence Committee: Liebau, Heike, “‚Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen‘: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängigkeitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914–1920)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019): 11 pp, https://www.projekt-mida.de/rechercheportal/reflexicon/.

Bibliography

Barooah, Nirode K., Germany and the Indians. Between the wars. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, 2018.

Fischer-Tiné, Harald, “Arya Samaj”. In: J. Bronkhorst, A. Malinar (eds.) Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section Two: India. Volume 22/5. Leiden: Brill, 2013, pp.389–396.

Framke, Maria, Delhi Rom Berlin. Die indische Wahrnehmung von Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus 1922–1939. Darmstadt: WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft), 2013.

Gould, William, Hindu Nationalism and the language of politics in late colonial India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Harvolk, Edgar, Eichenzweig und Hakenkreuz: Die Deutsche Akademie in München (1924–1962) und ihre volkskundliche Sektion. Munich: Münchner Vereinigung für Volkskunde, 1990.

Impekoven, Holger, Die Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung und das Ausländerstudium in Deutschland 1925–1945. Bonn: Bonn University Press, 2013.

Junginger, Horst, “From Buddha to Adolf Hitler. Walther Wüst and the Aryan tradition”. In: Horst Junginger (ed.) The study of religion under the impact of fascism. Leiden: Brill, 2008. pp. 105–177.

Kathe, Steffen R., Kulturpolitik um jeden Preis. Die Geschichte des Goethe-Instituts von 1951 bis 1990. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2005.

Liebau, Heike, “‚Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen‘: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängigkeitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914–1920)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019): 11 pp, https://www.projekt-mida.de/rechercheportal/reflexicon/.

Michels, Eckard, Von der Deutschen Akademie zum Goethe Institut. Sprach und auswärtige Kulturpolitik 1923–60. Munich: Oldenbourg, 2005.

Scholten, Dirk, Sprachverbreitungspolitik des nationalsozialistischen Deutschlands. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001.

Spang, Christian W., Karl Haushofer und Japan. Die Rezeption seiner geopolitischen Theorien in der deutschen und japanischen Politik. Munich: Iudicium, 2013.

Thierfelder, Franz, India Institute of the Deutsche Akademie 1928–1937. Munich: India Institute, 1937.

——–, “30 Jahre India Institut München. 1928–1958”. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Auslandsbeziehungen 2, Stuttgart 9 (1959): pp. 92–102.

Baijayanti Roy, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029