By Tobias Delfs

Published in 2021

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00009

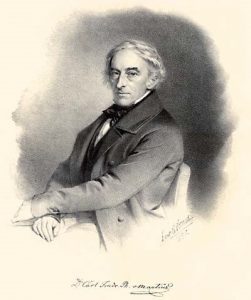

Image: A botanical drawing of the species Phaseolus fuscus from Wallich’s book Plantae Asiaticae Rariores. ttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Nathaniel_Wallich#/media/File:Plantae_Asiaticae_Rariores_-plate_006-_Phaseolus_fuscus.jpg

This is a translated version of the 2019 MIDA Archival Reflexicon entry “Das deutsche Netzwerk rund um den dӓnischen Botaniker und Superintendenten des Botanischen Gartens von Kalkutta Nathaniel Wallich (1786–1854)”. The text was translated by Rekha Rajan.

Table of Contents

Germans in the Colonies | The German-speaking World | Archives and Holdings | Published Sources | Secondary Literature

Nathaniel Wallich came from a German-Jewish family and studied medicine and botany in Copenhagen. In 1807, he left for Serampore near Calcutta in order to work as a doctor for the Danish trading company. When, the Danish town of Serampore was occupied by the British shortly thereafter during the Napoleonic Wars, Wallich was at first imprisoned. As a doctor, however, he was in demand in the colonies, especially among the Europeans, and he quickly established contact with influential people like the members of the Asiatic Society, the British Baptist missionaries William Carey and William Ward in Serampore, or the director of the Botanical Garden in Calcutta, William Roxburgh. His strong interest in botany was also helpful in establishing these contacts. Finally, it was both these aspects which helped to make him superintendent of the Botanical Garden in Calcutta in 1817. Over the following decades Wallich organised several research and recreational journeys, for example to Nepal and Assam, to Singapore, to the Cape Colony and to Mauritius. Meanwhile, his correspondence network became increasingly global, sporadically extending to the USA, Brazil and Australia (Krieger 2014, 2017a, Harrison 2011, Arnold 2008).

From 1828 to 1832 Wallich stayed in Europe and, with the permission of his employer the EIC, he distributed the plant collections and duplicates he had brought from India for evaluation by international experts for each of the relevant families of plants. He coordinated this work while staying in London. Time constraints alone made it impossible for him to single-handedly undertake an analysis of the material gathered. Therefore, he now involved renowned botanists from all over Europe (Krieger 2017a, Harrison 2011, Wallich 1830). Along with famous British names like George Bentham, William Jackson Hooker, Robert Brown or Robert Greville, one also finds in his correspondence names from Denmark, France, Switzerland and an entire list of researchers from the wider German-speaking world or Germans working abroad.

Wallich himself systematically catalogued his extensive correspondence which is now kept in the Central National Herbarium in the Botanical Garden of Calcutta in the form of a chronological index. This index also contains information about letters that are no longer traceable as well as additional biographical information about specific individuals that the botanist sometimes added. Unfortunately, the index ends in 1831 and is, therefore, incomplete. The letters themselves, which in most cases were addressed to Wallich, have also been bound chronologically in annual volumes (some volumes encompass several years). In many cases, the date of receipt and even the date of reply are noted on the letters. However, the paper is sometimes either in a poor or in a very poor condition. Some letters have come loose from the binding, are no longer in their original volume and are, therefore, difficult to date today if no date is mentioned, or if the date cannot be ascertained from the contents.

This makes it all the more important to consult other archives, which can be used to supplement the collection of letters in Calcutta. Besides the pertinent British and Danish archives, i.e. the holdings of their East India Companies, the various scientific societies, the Botanical Gardens in Kew (and elsewhere in Great Britain) as well as in Copenhagen, German archives, especially the papers in the estates of individual botanists, are useful. Occasionally they contain letters from Wallich himself, which are sometimes only available as a copy or a draft in Calcutta. Parts of the correspondence that are no longer available there, or are damaged, can also be found here. In addition, one finds discussions among the botanists about Wallich and India and about the worldwide exchange, so that holdings in Sydney or Cape Town, for example, also become relevant. With the help of these sources one can examine the practice and the actual process of botanical research and communication on India and beyond and the role of global networks, but also career strategies and structures of patronage of individual protagonists and institutions. The overarching question in all this concerns the participation of Germans in the imperial penetration of India. After all, even at this point of time German-speaking botanists participated in the empire of knowledge, profited from its collections and from international exchange and contributed to it with their own articles. With their scientific expertise they thus created or supported, consciously or unconsciously, the colonial management of eco-systems and, in end effect, also their exploitation. Botany was often closely intertwined with political and bureaucratic structures and both sides were dependent on each other.

Germans in the Colonies

In Wallich’s scholarly network, which was not just limited to people who only studied plants, but also included naturalists in general as also philologists and historians, German-speaking researchers occupy a considerable space. However, a distinction must be made between those on the spot, i.e. those who were quasi in the field as collectors in India or in other colonies and those who only shared material and corresponded with Wallich from study-rooms at home. The latter group mainly consists of university professors or people in charge of botanical gardens, while those in the former group could often also be amateur botanists who, along with their main job, for example as missionaries, as ship captains, as pharmacists or in the military, collected flora and fauna. The transitions were fluid. Wallich himself had been a doctor before he took over the Botanical Garden. A major component of his training, however, had also been botany (Krieger 2014). The same is also true for pharmacists who emigrated in large numbers to the colonies in the nineteenth century due to the lack of prospects in Europe. In addition to the correspondents already named, there were also Germans who did not themselves botanise, but who offered help, for example, by providing infrastructure and logistics, or by facilitating valuable contacts. For instance, in 1843 Wallich participated in a surveying expedition in South Africa, which he wanted to use for botanical excursions in the Cederberg mountains (Krieger 2017a). Ships often docked in the Cape Colony as a stopover station to and from India in order also to pick up provisions. Some German botanists and amateur explorers, like Adelbert von Chamisso, in 1818, also used this halt for smaller excursions and therefore sought contact with the many Germans living in Cape Town (Chamisso 1836), who were conspicuously recruited from the pharmaceutical industry and often also botanised. For his surveying expedition, however, Wallich contacted the Rhenish Mission at the South African Wupperthal mission station, named after the German town. From there local porters, ox-wagons and food supplies were organised. Often the missionaries were already in regions which the Europeans had not yet developed, or which were completely unknown. Thus, they could offer a base and local knowledge. In Wallich’s correspondence there is a map of the Cape Colony given to him by the Rhenish Mission in which the various stations of the different mission societies were marked. Conversely, the botanist and doctor helped the missionaries with medical problems since doctors were rare, particularly in rural regions.

Long before Wallich’s sojourn in South Africa, various German botanists had written to him from there, one of them being the well-known pharmacist Carl Ferdinand Heinrich von Ludwig, known as Baron Ludwig. This man from Württemberg had acquired considerable economic and political influence in the colonial society of Cape Town. His real passion, however, was to botanise, which led, among other things, to setting up a botanical garden that an increasing number of European guests came to visit (Bradlow 1965). He was constantly on the lookout for plants from all parts of the world for his garden, and he had also contacted Wallich in Calcutta in this context. Wallich was also contacted by German botanists Carl Wilhelm Ludwig Pappe, a doctor, as well as Karl Ludwig Philipp Zeyher and Christian Friedrich Ecklon, both pharmacists, living in Cape Town. In the latter cases, two ship’s captains had paved the way as personal connecting links so to speak on the route between Cape Town and Calcutta. In exchange for South Asian plants, the German botanists offered Wallich plants from South Africa. Wallich later visited all of them during his stay in Cape Town, and a brisk exchange took place with plants being redistributed, for example, to India, England, or Germany. Cape Town served as the nodal point for communication.

It is noticeable that in his correspondence with missionaries of the Cape Colony, Wallich does not deal with any botanical questions. This is in marked contrast to the correspondence with missionaries in South Asia who were active as collectors and partly also as scientists and who, for this reason alone, sought contact with Wallich and other naturalists. The Moravian Benjamin Heyne is one of them, as are Bernhard Schmid and others. Besides these, one would also have to name some German missionaries of the Danish-English-Halle mission which had been working since 1706 in and around Tranquebar. These missionaries were Christoph Samuel John, Johann Gottfried Klein, and Johann Peter Rottler, who had known Wallich’s predecessor, William Roxburgh, in Calcutta (Robinson 2008). Later, in Europe, Wallich also gave away parts of their India collections to German botanists for further study. By far the most important, however, were the British Baptist missionaries in Serampore who, unlike the missionaries in South India, were even geographically closer to Wallich and his family. The long-standing Danish-English-Halle mission was already in a period of decline, the Moravian Brethren had already left Bengal when Wallich arrived there and soon after they even left India. For the missionaries left in India, who lived in rather precarious circumstances, collecting and selling plants was sometimes a business model with good prospects. This was true, for example, of Schmid who, after the Church Mission Society could no longer support him in 1845, intended to set up his own botanical garden in the Nilgiri mountains and to sell plants from all over the world to England. The mission directors in Europe did not always approve of such activities. Despite this, a relatively large number of missionaries took part in the study of nature. They included, along with the groups already mentioned, also the missionaries of the Basel mission.

Military personnel in contact with Wallich were mostly from the British army. India-travellers who had a military orientation like Leopold von Orlich or Werner Friedrich Hoffmeister, who accompanied Prince Waldemar of Prussia on his journey through India, also briefly mention the Botanical Garden in Calcutta, the museum there, or even Wallich in their published travelogues (Orlich 1845, Hoffmeister 1847, Oriola 1853). However, Wallich’s correspondence does not contain any letters from them. Von Orlich is only mentioned indirectly. They were often concerned with economic topics such as opium cultivation in Patna. Hoffmeister and von Orlich were also in contact with Alexander von Humboldt. Hoffmeister wrote treatises on plants collected in India and on vegetation zones, and he also undertook his own measurements. He sent his Indian herbarium for evaluation to Johann Friedrich Klotzsch, custodian of the Botanical Garden in Berlin (Hoffmeister 1846, Garcke 1862).

German scientific explorers were far more significant, but they seldom received permission from the EIC to work in India. Rivalries certainly played a role in this, although many botanists demanded that the Germans be included to a far greater extent. It was more by chance that Wallich met Carl Theodor Philippi from Berlin, nephew of the botanist Rudolf Amandus Philippi. During his own South East Asian journey, C. T. Philippi temporarily took part in the Danish Galathea expedition which circumnavigated the world between 1845 and 1847, undertook some explorations on the Nicobar Islands and, among other places, also visited Calcutta. C. T. Philippi collected some molluscs that were later described by his uncle (Kabat, Coan 2017). In Calcutta, Wallich also gave the former some seeds and plants, which he sent on to Berlin where Alexander von Humboldt and some politicians, among others, distributed them to various botanists (Krieger 2017b). There is also some indication of Prussian colonial interests because Philippi even sent samples of different precious metals to Berlin. In Philippi’s opinion, the captain of the Galathea, Steen Bille, was also interested in a possible “cultivation” of the Nicobar Islands by the Danes (Bille 1852, 169). Wallich’s contact with the Bohemians Johann Wilhelm Helfer and his wife Pauline was far more intensive. Among other things, Helfer had taken part in Colonel Chesney’s Euphrates-expedition in 1836 and had then travelled on to India where he tried to obtain research commissions by highlighting specific themes in lectures. Ostensibly he was emphasizing – as the EIC wanted – mercantile interests, but his real motives also had to do with the study of nature (Nostiz 2004). Wallich was instrumental in paving the way for an expedition to Tenasserim financed by the EIC, for which Helfer received letters of recommendation and instructions from the botanist. In return, the explorer wrote to Wallich about the difficulties and the results of his journey, but he tried to be fair to all his sponsors by emphasizing his botanical interests to Wallich in particular, but by also working on questions of the search for raw materials (wood, mineral coal etc.) for Britain.

The German-speaking World

Wallich’s correspondence with people in the German-speaking world took place mainly during his sojourn in Europe between 1828 and 1832 and related to the generous distribution of the Indian plants he had taken with him. Before this period, there are only few such direct contacts, but after this some continued and developed into friendships. The botanist Johann Georg Christian Lehmann, professor for natural history and founder of the Hamburg Botanical Garden, and the professor of botany in Berlin, Karl Sigismund Kunth, even visited Wallich in London in order to get a first-hand impression of the Indian plants and also met his family in the process. Other botanists like Christian Gottfried Daniel Nees von Esenbeck of Bonn and Breslau (Wroclaw), director of the Leopoldina from 1818 till 1858, or Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius of Munich regretted not having done this, but they remained in active contact with Wallich even after he had returned to India. Accordingly, the correspondence that is accessible deals not only with specialist topics, but also touches upon, for example, family, health, or even political issues. Questions of competition and career were also significant aspects of the correspondence. Allegedly unjustified appointments, rivalries and other scandals in the universities and botanical gardens were mentioned, or attempts were made to place one’s own students or other acquaintances with Wallich in India. The connections were also based on the principle of reciprocal benefits. These included expectations of reciprocal citations, of plant exchanges and forewords, of translations, subscriptions and of the naming of plants after scientists. Lobbying in each other’s countries was also part of this since the 1830s was a period when there was growing pressure on British botanists to attune their work more to the interests of the economy and to the principle of usefulness (Drayton 2000).

The institutional dimension, therefore, was not only a question of membership in scientific academies, but also letters of thanks from or to state institutions. Acting upon Wallich’s advice and forwarded by him, von Martius sent the directors of the EIC a thank-you letter and his written works for the EIC library at the Calcutta Botanical Garden. At the meeting of German naturalists and doctors in 1830 in Hamburg, the botanical section resolved to follow Lehmann’s wishes and to send, as a mark of their gratitude, a joint letter each to the EIC, to Wallich and to the King of England. The letters were also accompanied by the request to allow Wallich to stay longer in Europe to better organise the publication of his works. Other official institutions were also involved in the scientific exchange. Through the director Heinrich Friedrich Link, the poet and naturalist Adelbert von Chamisso and the custodian Johann Friedrich Klotzsch the Prussian Minister of Culture, Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein expressed his thanks in 1837 to Wallich in Calcutta and Robert Wight in Madras for the collections placed at the disposal of the Neu-Schӧneberg Herbarium.

Indirect connections to individual botanists were also established. When, for example, Bernhard Schmid returned from India, he visited Jonathan Carl Zenker, professor of botany in Jena, and handed over the plants he had collected in India so that they could be described and drawn. Zenker had also established an India-section in the Botanical Garden in Jena. Schmid wrote a detailed letter to Wallich about this meeting. Botanists also often sought the help of their colleagues to forward a parcel when it was a question of using the fastest and most favourable route for sending plants or literature. Nees von Esenbeck asked Wallich to send him texts to Breslau (Wroclaw) through Lehmann in Hamburg. Wallich also had to forward plants to British colleagues, or Lehmann would facilitate transport to or from South Africa and from there to India. In this way one also shared information about botanist colleagues, regardless of whether one knew them personally or not.

Archives and Holdings

The Department for the History of Northern Europe at the Christian Albrechts University in Kiel offers an open access database with information about roughly 5000 letters of various provenances from and to Wallich. Data added includes author, addressee, place and date, wherever available, biographical data for the most important people, as well as the relevant archives. In addition to the Wallich documents, it is worthwhile to look at literary estates and autograph-collections of other German archives. Much of the material is accessible online in the Kalliope Union Catalog. As far as the Berlin holdings of Adelbert von Chamisso or Alexander von Humboldt are concerned, most of the documents can even be accessed online. Humboldt himself rarely appears in the Wallich holdings, but he seems to have often received botanical material and information from Wallich. Humboldt was, in general, extremely interested in India, and this resulted in his support for various India-travellers such as von Orlich and the Schlagintweit brothers. He himself could not travel to India due to opposition from the EIC.

Also interesting are the holdings of the Zoological Museum in what is today called the Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) in Berlin (Historical Department). Although the holdings that are organised by name (Zool. Mus.) do not contain any letter from Wallich, they do have some archival documents about Johann Wilhelm Helfer’s expedition to Tenasserim and the role played by Alexander von Humboldt in it. The same is true for Leopold von Orlich and his later attempts to serve as the intermediary for the natural history exchange between Berlin and India, or for the natural history specimens brought by Werner Hoffmeister. Unfortunately, most of the documents in the Berliner Botanischen Garten (Berlin Botanical Garden) were lost during the Second World War. Therefore, there is nothing to be found there on Wallich.

Rudolph Benno von Rӧmer’s extensive collection in Leipzig is of special interest. He was friends with the professor of botany Gustav Kunze, interested in botany after studying under Kunze and a famous collector. He left all his books on botany as well as his extensive herbarium to the Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig (Leipzig University library) where the holdings can be accessed today (UB Leipzig, Slg. Rӧmer/NL 133). Kunze’s literary estate is also available there (UB Leipzig, Nachlass Gustav Kunze Ms.0352) and, apart from some letters about Wallich’s India collection, it also contains correspondence with the botanists of the Cape Colony, some of whom had been Kunze’s students, with professorial colleagues and with Bernhard Schmid. The letters have been listed in Kalliope. The same holds true for the extensive correspondence of the botanist von Martius in Munich, which is kept in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library) in Munich (BSB Martiusana II A) and, compared to that of other German professors, contains the largest amount of source material on Wallich and India.

An overview of the holdings of the Hamburg botanist Lehmann are on the website of the Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg (State- and University Library Hamburg) (http://www.sub.uni-hamburg.de/sammlungen/nachlass-und-autographensammlung/nachlaesse-und-autographen-von-a‑z.html#c6563), which is storing parts of the estate (Nachlass Johann Georg Christian Lehmann, 1 Archivkasten, 1 Bd. NL Lehmann, Briefe an Lehmann (Thes. ep.: 4o : 65) und Diplome (Bd.); Adressat Briefe NJGL: B; Verfasser Brief LA (Literaturarchiv): Lehmann, Johann Georg Christian). Besides his Wallich-letters his correspondence with South Africa and his work as an intermediary are of great interest.

The letters of the India missionary Bernhard Schmid, on the other hand, are distributed across various archives and libraries. They can be found online in the well-catalogued Missionsarchiv der Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle (mission archives of the Francke Foundations at Halle) (AFSt/M), where other missionaries like John, Klein, or Rottler can also be found, as also in the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg (Heidelberg university library) and scattered in Nuremberg or Dresden or in Kunze’s estate in Leipzig. The missionaries particularly provide good insights into the concrete practice of collecting plants on site in India, the difficulties that arose therein, and the paths and distribution of the collections. Also of interest are the holdings of the Leopoldina in Halle related to its president Nees von Esenbeck, who was in close contact with Wallich and other botanists.

Published Sources

Bille, Steen, Bericht über die Reise der Corvette Galathea um die Welt in den Jahren 1845, 46 und 47. Aus dem Dänischen übersetzt, und theilweise bearbeitet von W. v. Rosen, 1. Bd. Kopenhagen, Leipzig: 1852.

Chamisso, Adelbert von, Reise um die Welt. 2 Bde. Leipzig: 1836.

Hoffmeister, Adolph (Hg.), Briefe aus Indien, von W. Hoffmeister, Arzt im Gefolge Sr. Königl. Hoheit des Prinzen Waldemar von Preussen; nach dessen nachgelassenen Briefen u. Tagebüchern. Mit einer Vorrede von C. Ritter und sieben topographischen Karten. Braunschweig: 1847.

Hoffmeister, Werner, “Ueber die Verbreitung der Coniferen am Himalayah, aus einem Schreiben des Dr. W. Hoffmeister an Hrn. v. Humboldt”. Botanische Zeitung 4 (1846), S. 177–185.

Klotzsch, Friedrich und August Garcke, Die botanischen Ergebnisse der Reise seiner Königlichen Hoheit des Prinzen Waldemar von Preußen in den Jahren 1845 und 1846 durch Werner Hoffmeister auf Ceylon, dem Himalaya und an den Grenzen von Tibet gesammelte Pflanzen. 2 Bde. Berlin: 1862.

Nostiz, Gräfin Pauline, Johann Wilhelm Helfer’s Reisen in Vorderasien und Indien. Berlin: 2004 (zuerst Leipzig: 1873).

Oriola, Eduard von, Heinrich Mahlmann, Zur Erinnerung an die Reise des Prinzen Waldemar von Preußen nach Indien in den Jahren 1844–1846. Die Illustrationen ausgeführt nach Reiseskizzen des Prinzen von Ferdinand Bellermann und Hermann Kretzschmer. 2 Bde. Berlin: 1853.

Orlich, Leopold von, Reise in Ostindien, in Briefen an Alexander von Humboldt und Carl Ritter. 2 Bde. Leipzig: 1845.

Wallich, Nathaniel, Plantae Asiaticae rariores, or, Descriptions and figures of a select number of unpublished East Indian plants. 3 Vols. London: 1830–32.

Secondary Literature

Arnold, David, “Plant Capitalism and Company Science. The Indian Career of Nathaniel Wallich”. Modern Asian Studies 42, 5 (2008): pp. 899–928.

Bradlow, Frank R., Baron von Ludwig and the Ludwig’s‑Burg Garden. A Chronicle of the Cape from 1806 to 1848. Cape Town: 1965.

Drayton, Richard, Nature’s Government. Science, Imperial Britain, and the ‚Improvement‘ of the World. New Haven: 2000.

Harrison, Mark, “The Calcutta Botanic Garden and the Wider World, 1817–46”. In: Uma Das Gupta (ed.) Science and Modern India: An Institutional History, c.1784–1947. Delhi: 2011, pp. 235–255.

Kabat, Alan R. und Eugene Victor Coan, “The Life and Work of Rudolph Amandus Philippi (1808–1904)”. Malacologia 60, 1–2 (2017): pp. 1–30.

Krieger, Martin, Nathaniel Wallich. Ein Botaniker zwischen Kopenhagen und Kalkutta. Hamburg-Kiel: 2017.

——–, „Die ‚Galathea‘ in Kalkutta. Naturforschung und koloniale Macht“. In: Oliver Auge, Martin Göllnitz (Hg.) Mit Forscherdrang und Abenteuerlust. Expeditionen und Forschungsreisen Kieler Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler. Frankfurt am Main: 2017, S. 23–36.

——–, “Nathaniel Wallichs karriere i Serampore og Calcutta 1808–1815”. Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift 2014, pp. 69–86.

Robinson, Tim, William Roxburgh. The Founding Father of Indian Botany. Chichester: 2008.

Tobias Delfs, IAAW, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029