Workshop Program

The workshop program can be downloaded as PDF file here.

December 12.–13. 2019

Centre for Modern Indian Studies (CeMIS)

Board Room (2nd Floor, Room 2.112)

Waldweg 26, 37073 Universität Göttingen

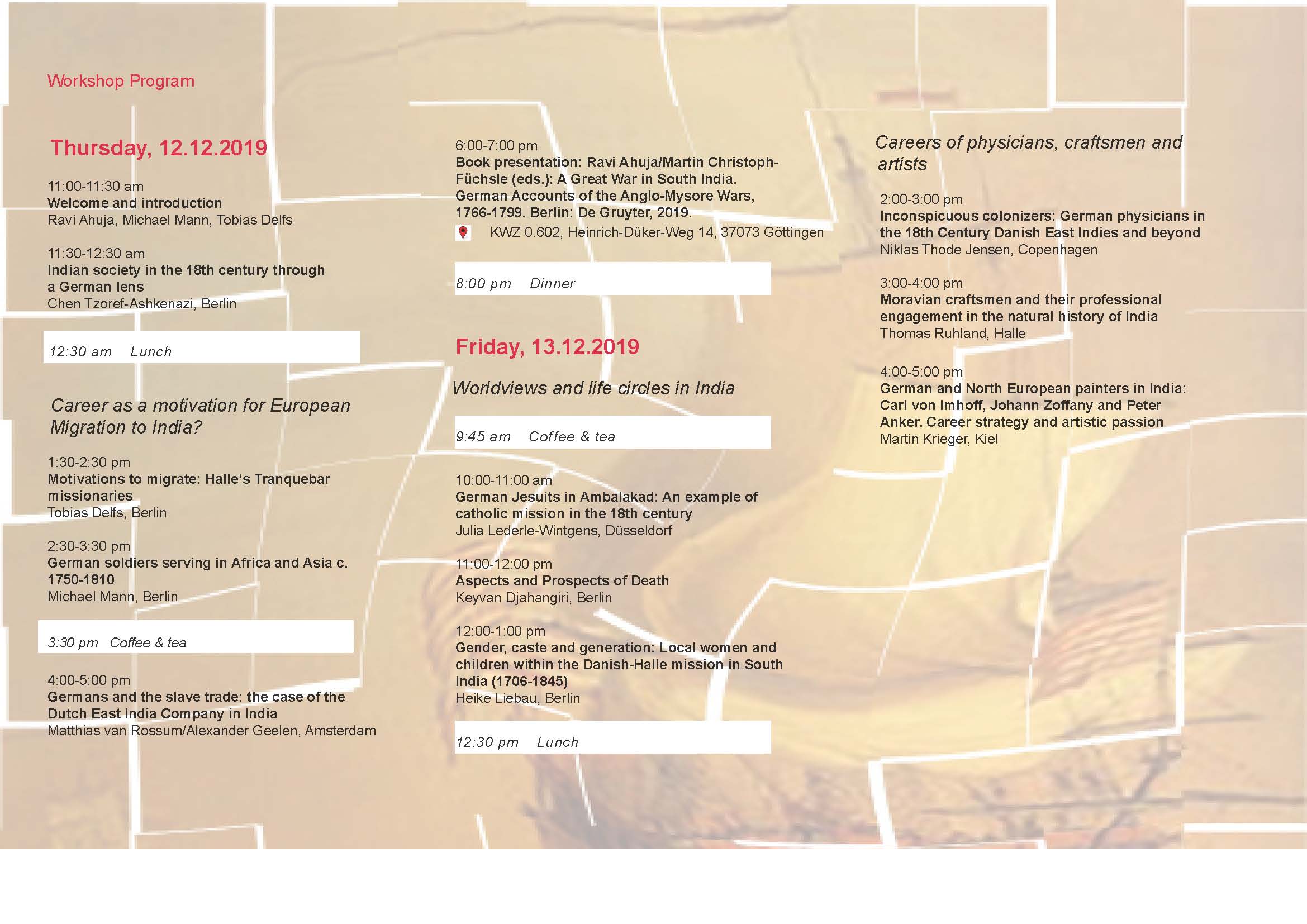

Thursday, 12.12.2019

|

11:00–11:30 am |

Welcome and introduction |

|

11:30–12:30 am |

Indian society in the 18th century through a German lens |

|

12:30 am |

Lunch |

Career as a motivation for European Migration to India? | |

|

1:30–2:30 pm |

Motivations to migrate: Halle‘s Tranquebar missionaries |

|

2:30–3:30 pm |

German soldiers serving in Africa and Asia c. 1750–1810 |

|

3:30 pm |

Coffee & tea |

|

4:00–5:00 pm |

Germans and the slave trade: the case of the Dutch East India Company in India |

|

6:00–7:00 pm |

Book presentation: Ravi Ahuja/Martin Christoph-Füchsle (eds.): A Great War in South India. German Accounts of the Anglo-Mysore Wars, 1766–1799. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019 |

|

8:00 pm |

Dinner |

Friday, 13.12.2019

Worldviews and life circles in India | |

|

9:45 am |

Coffee & tea |

|

10:00–11:00 am |

German Jesuits in Ambalakad: An example of catholic mission in the 18th century |

|

11:00–12:00 pm |

Aspects and Prospects of Death |

|

12:00–1:00 pm |

Gender, caste and generation: Local women and children within the Danish-Halle mission in South India (1706–1845) |

|

12:30 pm |

Lunch |

Careers of physicians, craftsmen and Artists | |

|

2:00–3:00 pm

|

Inconspicuous colonizers: German physicians in the 18th Century Danish East Indies and beyond |

|

3:00–4:00 pm |

Moravian craftsmen and their professional engagement in the natural history of India |

|

4:00–5:00 pm |

German and North European painters in India: Carl von Imhoff, Johann Zoffany and Peter Anker. Career strategy and artistic passion |

Workshop Abstracts

The workshop abstracts can be downloaded as PDF file here.

Germans in 18th Century India: A Social History of Everyday Life

Germans were already involved in the European colonial 15th and 16th century expansion into Asia: trading companies such as the Welser and Fugger supported the Portuguese financially and from 1502/03 onwards, Germans took a part in it directly. With the emergence of the various East India companies, this development intensified, and it was in the 18th century that numerous Germans moved to India. They did not only work as merchants, soldiers or sailors, but also as missionaries, naturalists, craftsmen, pharmacists, doctors or as painters–and even in the service of Indian princes. The transitions, however, could be fluent if, for instance, a missionary acted at the same time as a merchant, craftsman, teacher or natural scientist, or if doctors, missionaries or pharmacists took up botanizing. There were also real survivors with considerable social mobility, performing different jobs at different times.

The workshop will comparatively address this previously neglected diversity through group analyses or case studies. It will deal (1) with travel motivations, with the process of recruiting in Europe, with individual images of India and the demand for certain professional groups. In addition, it (2) will turn to the social stratifications themselves. In this context, it will investigate the question of differences to Europe and the representation of distinctions between professional groups, classes, “nations” or with regard to the Indien population of the time. Furthermore, the workshop (3) will shed a light on concrete living conditions, subjective perceptions and experiences in India and will compare these with the initial expectant attitude of a stay. Possible topics would be respective forms of coping strategies of Germans and other Europeans and their reactions to political, economic and social changes and catastrophes such as wars or famines. All of this raises the question of the extent to which German archives and sources can widen the view of historians dealing with the history of 18th century India.

Indian society in the eighteenth century through a German lens

Chen Tzoref-Ashkenazi, Berlin

Peter Joseph du Plat was a young officer sent to India with the 15th Hanoverian regiment in 1782 as part of the Hanoverian auxiliary troops in the second Anglo-Mysore War. In March 1784 he wrote a letter to a relative in Germany, whose manuscript is located in two German archives, in Hanover and Potsdam. The letter narrates the course of the military events in which the Hanoverian expedition participated and supplies a description of the conditions under which the Hanoverian soldiers lived in addition to a short description of Indian society. The manuscript is part of a significant corpus of ego-documents by Hanoverian officers, some of which were published at the time while others are kept in German archives in manuscript form, that combine narrations of military events with descriptions of Indian society. As the analysis of the text will show, similar to other German texts, du Plats understanding of Indian society was unsystematic, drawing on a combination of notions brought from Europe, British interpretations supplied by EIC and royal officers who had come earlier to India, information supplied by German missionaries, and his own personal experience. It is not easy to distinguish between these sources of influence. The outcome, however, is markedly different from official British representations of India. While obviously written from a European perspective, it does not always lend itself to the service of a colonial ideology. On the other hand, it is equally impossible to speak of a unified German perspective. The texts written by Hanoverian officers reflect a variety of individual perspectives that are not always easily distinguishable from similar British texts that did not serve explicit official or ideological purposes. It is, however, justified to consider the German texts, both by officers and by missionaries, as outsiders’ perspectives, because their authors did not, or only partially belonged to the colonial establishment, and felt much less committed to its cause than British authors usually did. As such, they enrich our understanding of European perceptions of and responses to Indian society beyond the much more often used reservoir of British texts.

Motivations to migrate: Halle’s Tranquebar Missionaries

Tobias Delfs, Berlin

Missionaries played a significant role in the European colonial expansion. In the case of eighteenth century India, it was mainly the missionaries of the Danish-English-Halle mission, most of whom came from Germany and where chosen by the Francke Foundations in Halle. While above all the older missionary historiography often portrayed them as being driven solely by missionary zeal, this paper questions such an assumption. It will examine possible further motivations of the candidates. On the basis of their personal history, their application documents, the internal communication in the mission centres, between the missionaries themselves and between the missionaries and the centres, it is examined whether specific images of India, career aspirations, lacking career prospects or concrete problems in Europe could be significant motives for the application. The paper looks at accepted as well as rejected candidates, the mission headquarters’ reasons for acceptance and rejection, as well as the discrepancies between missionary expectations and experiences in India.

German soldiers serving in Africa and Asia c. 1750–1820

Michael Mann, Berlin

Soldiers recruited from central European countries, or Deutschland, as contemporaries called the region, were part of a pan-European labour market in the long eighteenth century. In the early modern period German soldiers served in the armies of European monarchs and transcontinentally operating trading companies such as the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) and the East India Company (EIC). In addition, German princes hired out their armies or parts of their troops to create additional income and to participate in European politics. In the second half of the eighteenth century, western European continental and intercontinental colonial warfare in America, Africa and Asia caused a huge demand for additional troops. Many of them were recruited on the German labour markets. The paper will ask in how far becoming a soldier, whether serving in or outside Europe, was one of the many options men of different social backgrounds had trying to overcome dire economic conditions (pauperisation) in Germany. The paper will also ask whether becoming a soldier was part of a labour market based on various forms of dependent labour, be that slavery, serfdom, servitude, or soldiery. Like sevitude, for example, precursor of indentured labour systems of the nineteenth century, the labour of common soldiers was organised through contracts fixing terms of service including pay, duration and working conditions.

Germans and the slave trade: the case of the Dutch East India Company in India

Alexander Geelen and Matthias van Rossum, Amsterdam

This paper will explore the role and participation in the slave trade by Germans in the service of the Dutch East India Company. Slavery and slave trade was widespread throughout the VOC-empire, leading to the coerced circulation of enslaved people from South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Africa and Madagascar to and from different VOC-settlements. The Company was heavily involved in organizing the institution of slavery, and regulating and administrating the slave trade. Although the VOC also owned and transported slaves, most slave trade was undertaken by the European, Asian and Eurasian subjects and personnel of the Company. Employees from German speaking regions were recruited, and climbed, in important numbers into the lower and middle ranks of the VOC. There they worked as soldiers, sailors, writers, merchants and even mining specialists. This paper explores the participation in the slave trade by these German VOC-employees working in the VOC-settlements on the Malabar coast, especially Cochin (present-day Kochi, Kerala). This paper will use databases of slave transactions (Acten van Transport) and permits for export (Permissies) preserved for eighteenth century Cochin in the VOC-archives, and will contextualize its findings with information in court records, personnel administration, testimonies, and other sources. Exploring the slave trade and connections of German Company personnel in India can help further uncover the overseas experience of this often overlooked group.

German Jesuits in Ambalakad: An example of Catholic mission in 18th century Southern India

Julia Lederle-Wintgens, Düsseldorf

In their world-wide activities, the Jesuit order that was founded in 1540 soon became influential and powerful. Being a perfectly linked and highly mobile order, the Jesuits were able to build a unique network of communication and transfer. In India, the Society of Jesus relied on its exclusive relationship with the Portuguese crown for a long time. By the eighteenth century, however, Portugal was not able to protect and support the Jesuit mission stations outside of Goa anymore. Accordingly, the dominance of Portuguese members within the order diminished, too. In this context, the Collegium Maximum of Ambalakad became an interesting, but neglected, case of Jesuit acting in Southern India. A small group of mixed European Jesuits tried to become influential intermediaries. Focusing on the role of the German Jesuits of Ambalakad may illuminate these new ways of Jesuit mission in eighteenth century India.

Aspects and Prospects of Death

Keyvan Djahangiri, Berlin

The Lutheran Mission’s presence at the Danish seaport of Tharangambadi in today’s Tamil Nadu State is widely known and well-studied. However, regularly occurring but marginally studied social life phenomena, such as the dealing with death and dying, bid us to revisit source documents and dig for hidden patterns and buried procedures of everyday life history. The paper’s leading question, therefore, is what Alltagsgeschichte can and cannot tell us about different cultures cohabiting and interacting over a long period, such as the eighteenth-century multi-layered South Asian power shifts. Naturally, the question also addresses the possibilities and limitations of missionary reports. Digging into the mentioned sources the paper seeks to test two hypotheses: (1) Funerals as a cultural practice create identity and a sense of purpose. As with all cultural and social practices, the awareness of their indispensability and the conviction for their performance’s necessity are extraordinarily strengthened, when they are to be preserved in a foreign, insecure or even hostile environment. The same applies if cultural practices preserve and serve to delimitate and safeguard the own community against other cultures and religions. (2) Funeral rituals are a convenient and cohesive instrument of demonstrating and disciplining oneself (in front of others) – considering in particular its reference to afterlife and the fact that a cultural transfer of these practices is intended or takes place.

Gender, Caste and Generation: Local Women and Children within the Danish-Halle Mission in South India (1706–1845)

Heike Liebau, Berlin

When we explore the day-to-day practices at Christian mission stations, family life cannot be ignored. Although Mission history has turned towards social history, including family history, research so far has mostly focused on the life of European/American women with regard to the success of the mission and their social role within. Authors aim at challenging the notion of the marginality of women arguing against reducing their role to loving wives, caring mothers and friendly teachers. In contrast, my paper draws attention to local women and children of local mission workers in the context of the Danish-Halle Mission in the 18th, early 19th century. It explores social structures within the mission context, such as: a) the professional positions of local women (as domestic servants; bible women, teachers, or catechists), b) their position within the family, including their role as wives or widows of local male mission workers (co-working with their partners; continuing the work after their husbands´ death) and c) laws and regulations for female mission workers (payment, widow support). With regard to local children, especially children of local mission workers, I will explore the importance of inter-mission marriages and the promotion of “promising” children through a special system of sponsorship. Conceptually, I will situate my observations within broader debates on gender, caste and generation.

Inconspicuous Colonizers: German physicians in the 18th century Danish East Indies and beyond

Niklas Thode Jensen, Copenhagen

For Europeans travelling to and living in 18th century India, the risk of fatal disease was a fundamental part of everyday life. Consequently, European trading companies and colonial powers employed surgeons and doctors to take care of their staff on board the ships bound for the East and in their colonies. In the Danish East India Companies and royal administration of the East Indies, the majority of the physicians were Germans. Furthermore, the mission doctors of the Danish-Halle mission and Moravian mission in Tranquebar were also Germans. In the presentation, I will focus on this group of German physicians in Danish service in India and beyond. Since they have never been studied as a group, I will begin with a survey of their origins, career paths etc. to identify common patters and characteristics. On this basis, I will investigate two case studies that demonstrate some of the challenges faced by this group and their strategies for coping with them. The first case is Samuel Benjamin Knoll (1705–67, in India 1732–67), doctor of the Danish-Halle mission in Tranquebar. A closer study of his life and work reveals the difficulties of making a living as a physician in colonial India and problems of professional rivalry between European and Indian doctors. The second case is Johann Gerhard König (1728–85, in India 1768–85), doctor of the Danish-Halle Mission in Tranquebar, Royal Danish botanical collector and later natural history collector for the Nawab of Arcot and the British East India Company. König’s life reveals the importance of networks, mobility and being a ‘neutral foreigner’ in colonial India.

Moravian craftsmen and their professional engagement in the natural history of India

Thomas Ruhland, Halle

The various forms of missionary activity in India differed from one another not only according to the confession and the political allegiances of the missionaries and their wives and children, but also in the ways in which missionary communities were financed. Members of the Moravian South Asia Mission (1760–1802), for example, unlike the Jesuits or the members of the Danish-English-Halle Mission, for the most part needed to cover their own living expenses by themselves. In doing so, they relied not only on agricultural and craftsmen skills and on their craftsmen skills, but also on an extensive trade in natural specimens such as plants, shells, crabs, and reptiles. These natural objects were prepared and conserved in a variety of ways and were then made available for sale within India and in Europe. For some time, this activity could ensure the principal source of income for the “Brethren’s Garden” near Tranquebar and the mission on the Nicobar Islands. In producing these objects, the Moravian missionaries (usually themselves craftsmen such as cobblers and carpenters) worked closely with native people, who served as informants and helpers in the processing and naming of the natural specimens. My presentation will explain this practice, hitherto seldom explored in the missionary context, and will clarify the motives behind the collection of natural objects as well as the problems and other consequences. These included the newly resulting opportunities for Europeans and Indigenous to find employment with the (British) East India Company, as well as the effects on Indian employees of the Moravians such as Krishna Pal, who, after working with the Moravian missionaries in the field of natural history, became the first convert of the Baptist Missionary Society under W. Carey.

German and North European painters in India: Carl von Imhoff, Johann Zoffany and Peter Anker. Career strategy and artistic passion

Martin Krieger, Kiel

During the latter half of the eighteenth century, a colonial art-market emerged in India. Notably Calcutta with its abundance of financial wealth attracted artists from Great Britain and beyond. The collection of oil paintings and drawings preserved inside the Victoria Memorial at Calcutta still bears witness to this fact. A number of German and North European artists joined this trend and established their workshops in India. The Germans Carl von Imhoff and Johann Zoffany as well as the Norwegian Peter Anker render prominent examples and will be studied in detail here. Their social background, education and motivation for travelling to India will be scrutinized. Furthermore, it will be asked: To what degree did their activities in India contribute to enhancing their careers? Imhoff’s, Zoffany’s and Anker’s artistic oeuvre simultaneously played a role in creating a distinct image of India in Germany and Northern Europe. Against this backdrop, this paper will simultaneously ask for their impact on shaping contemporary ideas of India in Weimar, Copenhagen and other cultural centres.