By Razak Khan

Published in 2018

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00039

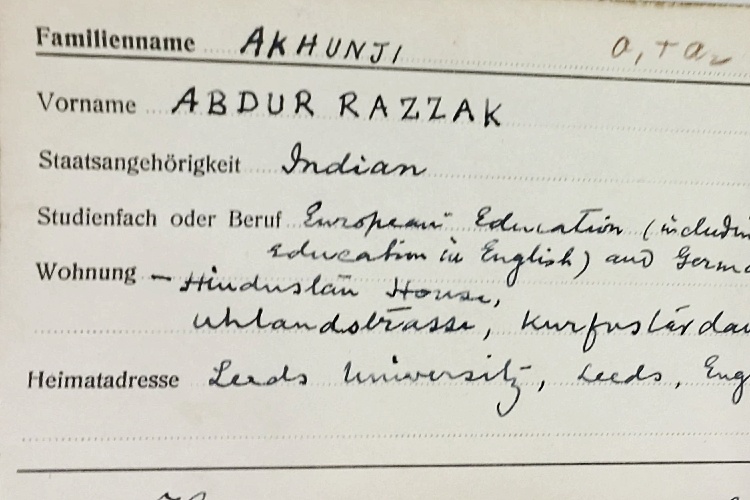

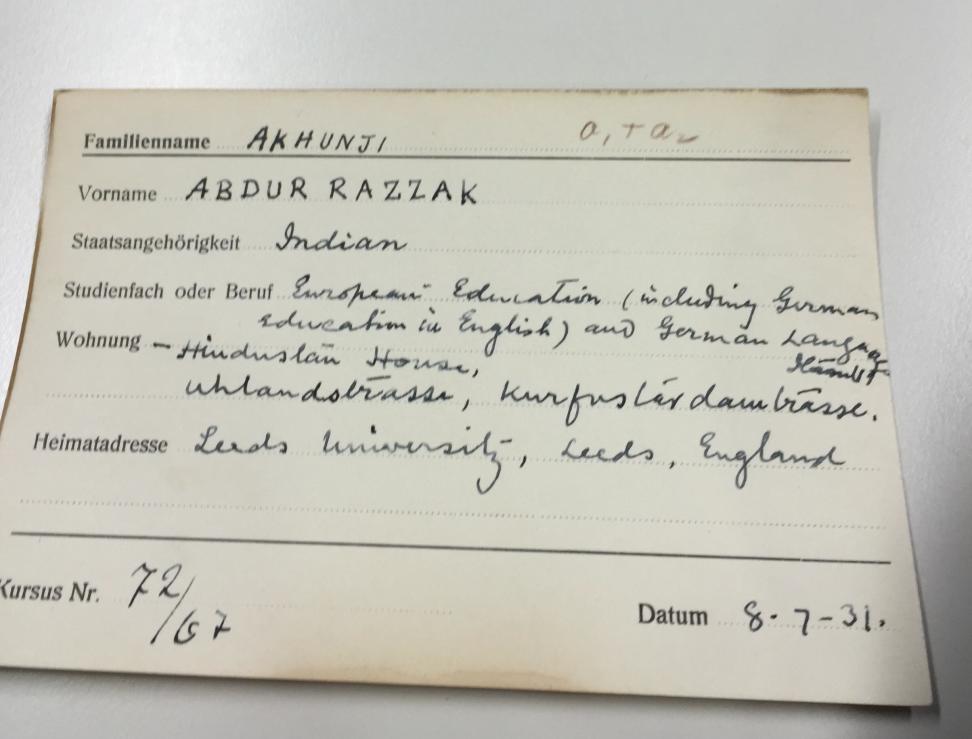

Image: HU UA, Ausländerkartei Indien, 1928–1938; Courtesy: Archiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Photograph by author.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Institutions, Actors and Networks | Affective Archive: Memory and Biography | Conclusion | Appendix | Notes | Bibliography

Introduction: Institutions, Actors and Networks

The Archiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin located at Wagner-Régeny-Straße 5, 12489 Berlin[1], provides useful information about intellectual entanglements spread across educational connections at the University. In this brief post, I examine some archival sources pertaining to South Asian students to make a case for entangling archives of educational institutions with the personal biographical affective archives to explore creative intellectual entanglements. My focus will be on South Asian Muslim students whom we encounter both in institutional archives as well as in rich affective biographical accounts left behind by them.

The Humboldt-Universität’s archival collection is undergoing digitization and is now searchable through finding aids and online archival data search.

https://www.archiv-hu berlin.findbuch.net

However, the generic keyword search on India and Indians is not very fruitful. It is better to use the German keyword Ausländer as well as Indien/Inder/indisch. A search conducted with these keywords leads to general results and not specific ones. However, documents on individuals can be accessed if adequate details like full name and year of study are provided to archivists. I was able to find information about Indian students in an un-catalogued selection of cards Ausländerkartei Indien, 1928–1938, The Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin archive. The archivist provided me with student cards that have been assembled prior to the digitization project. These enrollment cards are the most important source of information, especially about Indian students who registered with the Deutsches Institut für Ausländer (German Institute for Foreigners) for study-related issues, particularly German language-learning (See appendix for the full list). Further, documents on doctoral students can also be found through an index search of the faculty and departments records if full names and the year(s) of study are known. The cards also reveal the names of their local hosts and their residential addresses, giving a sense of the lives of Indians in Berlin. I found the cards very useful to reconstruct lived inter-cultural aspects of this history of South Asian students as it provides details under the following categories:

Familienname

Vorname

Staatsangehörigkeit

Studienfach oder Beruf

Wohnung

Heimatadresse

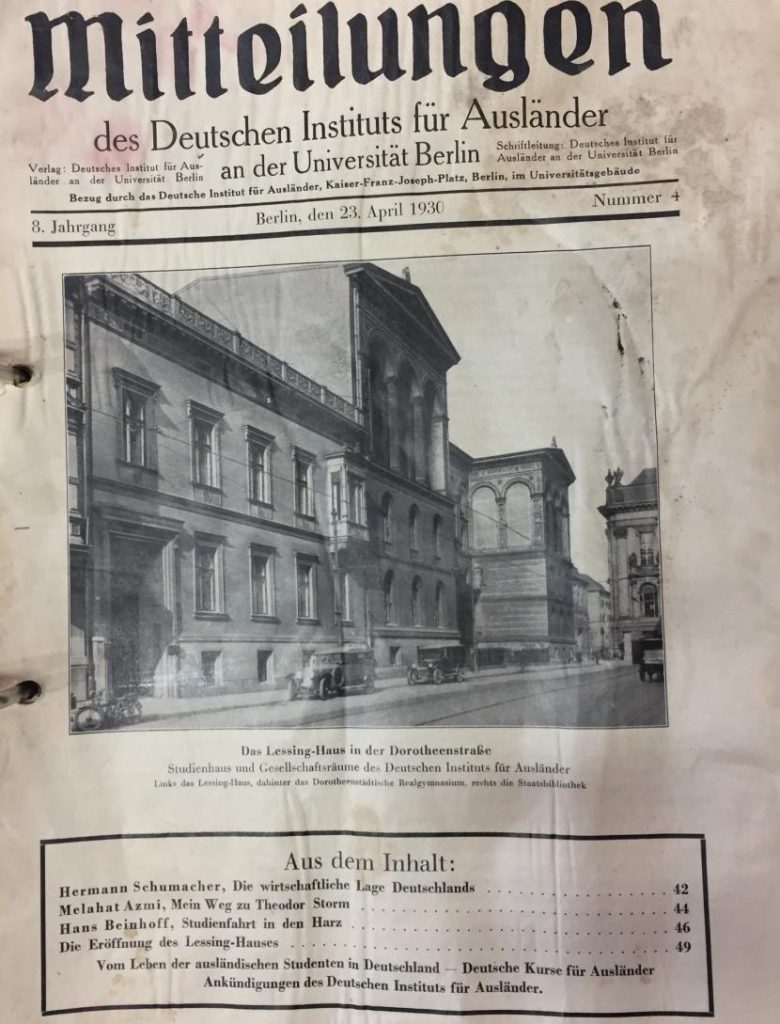

I also consulted the copies of the Institute’s magazine, which provides further details about the social, cultural and intellectual life of international students in Berlin. Hindustan Haus was sponsored by the German Institute for Foreigners at Berlin University. The institute also established the Hegel Haus for international student housing; provided German language courses and cultural activities for foreigners; and published a magazine that reflected student views and chronicled their experiences. These instances of institutional interactions for and of Indian students have been archived and documented at the Humboldt University archives.

The Hegel Haus was located in the center of Berlin Am Kupfergraben 4a, close to the university campus. Its urban location and character allowed foreign students to get acquainted with German language and culture as quickly as possible. It offered accommodation and food to the guests and provided services that facilitated orientation in the city. Among the tenants were also German students, who volunteered to host the foreign students. The house had 50 rooms, a garden, and a dining room. Numerous communal and social rooms, such as lecture halls, games’ rooms, reading rooms and a library were available on the premises. The sports hall and the baths were spacious. The rent for the rooms with full board, light and heating ranged between 125 and 160 RM monthly. Indian students like Bhairava Nath Rohatgi, Hem Raj Anand and Arjun K. Patel lived at the Hegel Haus Am Kupfergraben. Beyond the Hegel Haus, managed by the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin, international students also inhabited other parts of the city such as the middle class cosmopolitan parts of Charlottenburg as well as more affordable working class neighborhoods of Wedding and Moabit.[2] Details of individual students and their social and professional life can be gleaned from this list as well as from the images of the University magazine collection. Moving beyond institutional archival taxonomies affords an enlarged view of personal and public histories that are characterised by felt experience and emotions. I aim to strike a dialogue between institutional repositories and affective archives that foregrounds the entangled nature of officially chronicled and individually experienced histories.

Affective Archive: Memory and Biography

Autobiographies are interesting but difficult archival sources – lying at the intersection of history and memory, remembrance and forgetting. They are one example of what one may call “affective archives” of experiencing and narrating history. Human lives and personal and professional relations define these histories. Emotions and feelings give texture to these affective archives. They produce their own affective temporalities, geographies and, thus, histories. Autobiographical sources provide a particularly rich archive to understand the many entanglements, personal and professional, knitted between South Asian Muslim students and German intellectuals in the twentieth century. I shall attempt to give a sense of these affective histories by connecting University archives as well as personal affective archives in the form of autobiographical literature produced by South Asian Muslim intellectuals and through their relationships and networks in Germany.

Ann Cvetkovich has written insightfully about what she calls the “archive of feelings” that incorporates not just public facts but also personal memories chronicled through oral and video testimonies, memoirs, letters and journals. She elaborates that the archive of feelings is also “embedded not just in narrative but in material artifacts which can range from photographs to objects.”[3] Cvetkovich has also reflected on the larger question of archive and history writing to call for ”[a] radical archive of emotion in order to document intimacy, sexuality, love and activism – all areas of experience that are difficult to chronicle through the materials of traditional archive.”[4] Kris Manjapra notes the possibilities of and problems in writing entangled histories of South Asian intellectuals in Germany: “The archives are less detailed, but the affective bonds of political, social and intellectual entanglements between Germans and Indians in the war years is still obvious.”[5] Indo-German connections were forged and sustained both in regulated institutional contexts but also in affective personal ways. I explore these affective histories and archives by looking at institutional connections between Indian Muslim intellectuals and their German counterparts in the university context and by illuminating personal relations and friendships initiated through their interactions as teachers and students that led to their evolution as intellectual interlocutors and innovators.

The institutionalized documents can be connected with the affective archives constituted by autobiographical writings of lived experiences, felt emotions and memories as narrated by South Asian students and visitors to Berlin. The student cards reveal the diversity of religion, scholarly interests and social location of South Asian students. My focus here is on Muslim students due to the availability of archival sources in both institutional and personal archives. However, this post also shows that “South Asian Muslims” were not a homogenous category and were distributed across political, cultural and intellectual axes that connected them with other German and transnational actors and ideas.

The everyday student life in interwar Berlin is vividly described in the writings of Sayyid Abid Husain, Muhammad Mujeeb and Khwaja Abdul Hamied.[6] These attest to the fact that there was a noticeable and lively South Asian student community in 1920s Berlin.[7] Even Mirza Azeez, the Imam of the local mosque in Lahore, was studying chemistry in Berlin. He lived in the Ahmadiyya Mosque at Brienner Straße 7/8, Wilmersdorf in 1932.[8] Not unlike our own times, the typical student life was marked by a struggle to find cheap accommodations. There were also student gatherings and New Year parties.[9] Indian students also interacted with other student networks like the Association of Students for Central Europe in Berlin.[10] Abdul Sattar Kheiri and Abdul Jabbar Kheiri were well known as “Pan-Islamists” within the Indian circles. Habibur Rahman was one of the main figures of the Indian Muslim community as part of the “Jamiat al-Muslimeen in Berlin” (Islamische Gemeinde Berlin). There were also revolutionaries among the students like Maulana Barkat Ali.[11] Virendranath Chattopadhyay House was the center that brought together what scholars have classified as “revolutionary Indians,” “Indian Students” and “official circles” at house gatherings. We get a vivid account from autobiographical writings about the everyday struggles of student life, including the struggle to pick up German at the state school of foreign languages or finding partners for practicing the language. Hamied also met Tara Chand Roy – the Hindustani teacher at the foreign languages school.[12] He enrolled for a PhD in chemistry with Prof. Arthur Rosenheim. With Prof. Eduard Spranger, the examiner of his Verstand exam, he found intellectual affiliations through his work on the philosophy of understanding.[13] He also became close to the renowned chemistry professor Prof. Walther Nernst, Nobel Prize winner Prof. Fritz Haber as well as Prof. Budenstein and Prof. Freundlich. Prof. Budenstein took his students to manufacturing units while Prof. Ratheim introduced Hamied to the industrial soap and perfume factory of Dr. Schleich, where Hamied eventually interned and acquired first-hand experience in chemistry. This had a foundational influence on Hamied’s future career choice.[14] Apart from professional work experience, Hamied also shared fond memories of picnics and Christmas parties organized by Prof. Rosenheim. The reception parties on graduation brought students and professors together at the Hotel Bristol at Unter den Linden.[15] The connections forged with professors survived after the completion of formal studies. Hamied became an assistant to his teacher Prof. Volmer and through him got professional training in the school of pharmacy and the laboratory of Professor. Thoms in Dahlem. Hamied would go on to establish India’s biggest pharmaceutical company i.e. The Chemical, Industrial & Pharmaceutical Laboratories (CIPLA) in 1935.[16]

The student social and cultural life was vibrant and marked by gatherings and celebrations – another important site for forging connections and networks. These included Easter holiday gatherings or summer picnics at Spandau lakes where Hamied encountered his future love Lubow Derchanska, a young Polish communist Jew of Lithuanian descent.[17] Through Lubow, he discovered and also interacted with the larger networks of Russian and Jewish Communist leaders who frequented Berlin at the Roter Klub (Red club).[18] The Muslim-Jewish romance blossomed and on June, 1928 Hamied married Lubow in the Berlin mosque. In a remarkable gesture of religious harmony, the marriage ceremony was performed by Mr. Durrani, Imam of the Qadiani Mosque in Berlin.[19] Thus, the cultural and social milieu of Berlin brought together otherwise separated actors and networks.

Conclusion

As Gerdien Jonker´s work has shown these personal histories of inter-religious dialogue, love and marriage have been preserved in the Ahmadiyya mosque and needs to be taken into account in writing about German and South Asian entangled archives and histories.[20] Hamied and Luba´s Berlin memories are now also preserved in the visual archives and sound recordings and papers in the CIPLA archives as well as in the Films Division Archives in Mumbai. Thus, strands that run deep in personal lives have been drawn from institutional entanglements, which have been fondly narrated in affective archives needs to be brought in conversation with the more conventional institutionalized archives in writing affective entangled histories.

Appendix

South Asian Students in Berlin during World War I and in the Interwar Period.

The Categories used in the list as well as the entries correspond to those at the original University Registration Cards.

Due to the amount of data and display-related problems, the list is separately available here.

Notes

| [1] | https://www.ub.hu-berlin.de/en/locations/archive/collection-and-service/university_archives |

| [2] | Joachim Oesterheld. „Aus Indien an die Alma mater berolinensis — Studenten aus Indien in Berlin vor 1945“, In: Periplus 2004, Jahrbuch für Außereuropäische Geschichte (14. Jahrgang), Münster 2004, pp. 191–200. Kris Manjapra, Age of Entanglement: German and Indian Intellectuals across Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014, p.93. |

| [3] | Ann Cvetkovich. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke University Press, 2003. |

| [4] | Ibid.,241. |

| [5] | Kris Manjapra, Age of Entanglement, p. 97. |

| [6] | Muhammad Mujeeb, D. Zakir Husain: A Biography. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1972. Sayyid Abid Husain, Sughra Mahdi, Ḥayāt‑i ʻĀbid : k̲h̲ud navisht‑i Ḍākṭar ʻĀbid Ḥusain. Na’ī Dihlī : Maktabah-yi Jāmiʻah, 1984. K.A Hamied, A Life To Remember: An Autobiography. Bombay: Lalvani Publishing House, 1972. |

| [7] | K.A Hamied, A Life To Remember,.pp. 36–37. |

| [8] | Gerdien Jonker, The Ahmadiyya Quest for Religious Progress: Missionizing Europe 1900- 1965: Leiden : EJ Brill, 2016. |

| [9] | K.A Hamied , A Life To Remember: An Autobiography. Bombay: Lalvani Publishing House, 1972. Ibid., 46–48. |

| [10] | Ibid., 36. |

| [11] | Ibid., 36. |

| [12] | Ibid.,35. |

| [13] | Ibid., 31. |

| [14] | Ibid.,44. |

| [15] | Ibid.,33. |

| [16] | Ibid.,55. |

| [17] | Ibid., 41 |

| [18] | Ibid., 42 |

| [19] | Ibid., 73–74 |

| [20] | Gerdien Jonker, Entangled Archives and Memories: The Place of the Lahore-Ahmadiyya Mosque in the Indian-German Entanglement in Interwar Berlin. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Forthcoming. |

Bibliography

Cvetkovich, Ann, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke University Press, 2003.

Hamied, K. A., A Life To Remember: An Autobiography. Bombay: Lalvani Publishing House, 1972.

Husain, Sayyid Abid, Sughra Mahdi. Ḥayāt‑i ʻĀbid : k̲h̲ud navisht‑i Ḍākṭar ʻĀbid Ḥusain. Na’ī Dihlī: Maktabah-yi Jāmiʻah, 1984.

Jonker, Gerdien, The Ahmadiyya Quest for Religious Progress: Missionizing Europe 1900- 1965. Leiden: EJ Brill, 2016.

Manjapra, Kris, Age of Entanglement: German and Indian Intellectuals across Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Mujeeb, Muhammad, D. Zakir Husain: A Biography. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1972.

Oesterheld, Joachim, „Aus Indien an die Alma mater berolinensis — Studenten aus Indien in Berlin vor 1945“. Periplus 2004, Jahrbuch für Außereuropäische Geschichte (14. Jahrgang), Münster 2004, S. 191–200.

Razak Khan, MIDA, CeMIS, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029