By Heike Liebau

Published in 2022

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00048

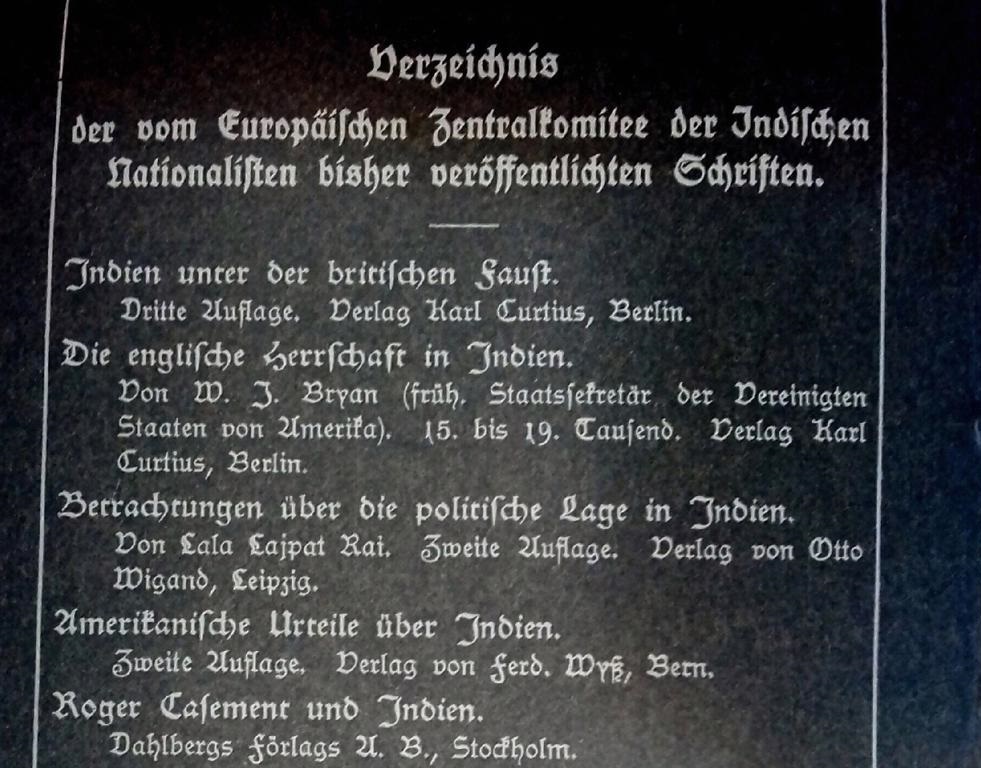

Photo: Verzeichnis der vom Europäischen Zentralkomitee der Indischen Nationalisten bisher veröffentlichten Schriften.

This is a translated version of the 2019 MIDA Archival Reflexicon entry “‘Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen’: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängigkeitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914–1920)”. The text was translated by Rekha Rajan.

Table of Contents

Genesis of an Archival Holding | India in German Foreign Policy during the World War | The Indian Independence Committee: Goals and Networks | “Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen in den Gebieten unserer Feinde. Indien” and other relevant file collections in the PA AA | Endnotes | Secondary Literature

Genesis of an Archival Holding

Supporting anti-colonial forces globally was an important element of the German foreign policy strategy during the First World War. It consisted not only of propaganda at various levels but also of financial and military- logistical aid. The policy aimed at picking up on and strengthening anti-colonial sentiments, and thus ultimately supporting unrest and upheavals against the wartime adversaries England, France and Russia. In short, the policy aimed to “instigate” and “revolutionize” enemy territories.

In the Information Service for the Orient (Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient, NfO) specially created at the Foreign Office, the orientalist, archaeologist and diplomat Max Freiherr von Oppenheim (1860–1946) initially developed a special strategy for “instigation” in Muslim areas, but this was soon extended to other colonies and territories under British, French or Russian rule. The historian Fritz Fischer later called this foreign policy propaganda strategy a “revolutionization programme” and showed how “revolutionization” was used by the German side as a means of warfare.

The aim of the war, to break up the British and the Russian empire, was combined with “revolutionization” as a means of warfare. France and England appeared to be most vulnerable in their coloured colonial peoples while the different foreign nationalities in Russia offered a starting point for instigating insurgencies.

(Fischer 1984: 109)

The Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, Berlin (PA AA), contains extensive files on World War I, arranged by country or region and entitled “Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen gegen unsere Feinde”. These contain a detailed documentation of German efforts to support revolutionary and nationalist forces with an anti-colonial or anti-imperial thrust. The aims of such efforts directed against the British, French or Russian imperial powers were easily compatible with the military and political goals of German foreign policy. It was a global strategy which also included neutral countries as the documents in the Foreign Office archives show. Under the title “Undertakings and Instigations against our Enemies” the holdings Weltkrieg 11 (WK 11) [World War 11] contain files on support for anti-Russian activities in the Ukraine (WK 11a); in Poland (WK 11b); in Russia, especially in Finland (WK 11c) or in the Caucasus (WK 11d); support for anti-colonial movements in Afghanistan and Persia (WK 11e); in “Egypt, Syria and Arabia” (WK 11g); Canada (WK 11i); among the Boers (WK 11j); among the Irish (WK 11k); “in the African territories of France” (WK 11l); “in Siberia” (WK 11m); in Romania (WK 11n); in Bulgaria (WK 11o); in Italy (WK 11p); in Spain (WK 11q); “in Abyssinia” (WK 11r); in Portugal (WK 11v) and in India (WK11f).

The Foreign Office and the Information Service for the Orient did not organise these propagandistic, military, logistical or financial “actions” alone, but carried them out with internationally operating networks, which had an anti-colonial or anti-imperial orientation. Corresponding groups in Berlin played an important role, which, for their part, were interested in weakening colonial powers from exile and in a purposeful cooperation with Germany. To this end, the Foreign Office, the NfO, and Department IIIb of the Political Section of the Deputy General’s Staff of the Army under Rudolf Nadolny (1873–1953) observed and monitored potential cooperation partners and made use of already existing organisational structures and networks of anti-colonial groups in Europe and North America. They supported the formation of independence committees that were monitored and controlled by the Germans, but which in turn tried to evade this monitoring and control and pursued their own political strategies.

The files in the PA AA with the title “Undertakings and Instigations against our Enemies. India” provide information about the origins, composition and the activities of the Indian Independence Committee in Berlin (IIC), established in September 1914, about its collaboration with the Foreign Office and with its associated international networks. Compared to other countries, India is the country with the most extensive collection of documents on the theme “Instigations” in the PA AA. The files on India within the WK 11 holdings begin with volume 1 in August 1914, with the shelf-mark R 21070; the last file in volume 48 with the shelf-mark R 21118 ends in April 1920. In addition, there are four sub-files with details about people for the same period (R 21119 to R 21122).

India in German Foreign Policy during the World War

As the largest colony of the British empire, India played a special role in the strategic plans of the German Foreign Office. The guiding thought for the German side was that unrest in India would considerably weaken the British empire. Relevant assessments of the situation were gathered from various sources. In analyses, which the Foreign Office commissioned at the outbreak of the war, German and Indian experts described the situation in India and gave their opinion on the question that was most decisive for the Germans, namely whether uprisings and revolts against the English were to be expected there in the near future and which forces should be supported in this context. The German Arabist and Islam-scholar Josef Horovitz (1874–1931), who had previously taught for several years in the Muhammedan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligarh, elaborated on the special role of Indian Muslims in a memorandum. He was of the view:

[…] that the Mohammedans in North India represent the more masculine element and if one wanted to create problems in the northern part of India it was essential to influence this component of the population, namely with reference to the pan-Islamic movement and the affiliation to the Ottoman Caliphate.[1]

The views of Indian political activists outside the sub-continent were also obtained. One of them was Chempakaraman Pillai (1891–1934), who had established and headed the international committee Pro India in Zurich and who had moved from Switzerland to Berlin in September 1914. He stated that an uprising was imminent in India.[2] Even Har Dayal (1884–1957), co-founder of the Ghadar Movement (English: Revolution) in North America and who was already in Europe by then, was convinced that a revolution was to be expected in India very soon.[3] Both Har Dayal and Pillai became active members of the IIC. It was the first of several independence committees of foreign groups in exile in Berlin and was followed, among others, by committees of Persian, Egyptian, Georgian or Irish nationalists (Bihl, 1975). These committees were formed with the help of the Foreign Office, especially the NfO. As far as the practical cooperation with German authorities was concerned, however, these committees increasingly eluded German control in the course of the war and pursued different, nationalist goals.

During the First World War, Berlin became an important centre for the political activities of Indian nationalists and revolutionaries. When the war broke out Indians, who were in Germany or in Europe in the summer of 1914, expected that they would get active support from Germany for their anti-colonial struggle. The German government authorities, for their part, associated this cooperation with the hope of strengthening anti-British forces and expanding their own positions during the war and beyond. This was in line with the dominant German military and foreign policy strategy, which Fritz Fischer characterised as the “programme for revolution”. In Fischer’s view, revolution was indeed a goal of the war that was directed at a support of anti-colonial forces and thus a weakening of the European colonial powers, i.e. Germany’s wartime enemies (Fischer, 1984; Jenkins, 2013). One way to implement this goal was by “instigating” anti-colonial groups globally. It included support for Flemish, Irish or Persian nationalists as also cooperation with Georgian, Egyptian and Indian anti-colonial political forces. The German “Jihad-strategy”, initially developed by Max von Oppenheim and intensely discussed in the international academic world (Loth, 2014; Lüdke, 2015; Zürcher, 2016), was merely one, albeit central, component of a more comprehensive imperial foreign policy.

The Indian Independence Committee: Goals and Networks

A look at the founding process of the Indian Independence Committee makes it clear that the organisers were able to draw on existing resources. Pre-existing translocal political networks and structures were partly relocated to Berlin and reorganised. Other places like London and Paris, which had earlier played an important role in political work, became too dangerous for (not only Indian) anti-colonial activities when the war began. With the help of the NfO, the Berlin Indian Committee established contact with the Ghadar Movement, which had come into being in 1913 in California, as well as with existing European networks of Indian revolutionaries in London, Bern, Geneva and Zurich in order to recruit members for the newly-established committee. Chempakaraman Pillai, who had established the Pro India Committee in Switzerland and had also published the newspaper Pro India there; Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, who had begun academic studies in Germany in 1914; as well as Har Dayal, who had co-founded the Ghadar Movement; and others provided further contacts. More than 50 names were associated with the IIC over time, including Abhinash Chandra Bhattacharya, Tarachand Roy, Mansur Ahmad, Maulavi Barkatullah, Taraknath Das, Birendranath Dasgupta, Bupendra Nath Dutta or the brothers Abdel Jabbar Kheiri and Abdel Sattar Kheiri, who were mainly active in Istanbul (Manjapra, 2014; Fischer-Tiné, 2015; Liebau, 2011a, 2014a; Oesterheld, 2004).

The IIC’s most important tasks, at least during the first half of the war, reflected both the interests of the anti-colonial activists as well as the expectations and goals of the Foreign Office. One of the defined goals was to organise a mission to Afghanistan which would seek the Emir’s permission to use Afghan territory for launching an attack on India with an armed Indian battalion. Members of the IIC were involved in the famous Afghanistan Mission of 1915 led by Werner Otto von Hentig (1886–1984). Furthermore, a mission to the Persian Gulf was to be organised to convince Indian soldiers there to not fight against Turkish troops. There was also a plan to win over volunteers for an Indian Legion by carrying out propaganda among the Indian prisoners-of-war in Mesopotamia. Anti-British propaganda was also to be organised among South Asian prisoners-of-war in Germany in order to gather prisoners to fight in the Turkish army. Members of the Berlin Independence Committee took part in producing the propaganda camp-newspaper “Hindostan” in Hindi and Urdu, which was distributed in the Halbmondlager (“Half Moon Camp”) in Wünsdorf, a camp set up specially for Muslims (Oesterheld, 2004; Liebau 2011a/b; 2014 a/b; Jenkins/Liebau/Schmid, 2020).

The Turkish side and the group of Indian nationalists operating from Istanbul played a decisive role in the functioning of the IIC. Shortly after the committee was formed in Berlin, a similar committee was also established in Istanbul. Members sometimes switched between the locations. Disputes over positions, hierarchies and strategies of action, as well as religious differences were the order of the day. Varying assessments of the political situation in Europe and in India and diverse alliances led to further tensions. In the background, the German Federal Foreign Office and the Turkish intelligence service, Tashkilat‑e Mahsusa, pulled the strings. During the war, it became obvious that the plans to revolutionize India and the German Jihad-propaganda were not yielding the expected success. The efforts of German imperialism to instrumentalize anti-colonial freedom movements had failed. The committees realized that the expectations they had from the German support would not be fulfilled. The IIC reacted by looking for new places to work in Switzerland, the Netherlands or Sweden. In 1917, Virendranath Chattopadhyaya opened a new office in Stockholm, which operated under the name Indiska Nationalkommittéen. This new committee engaged in a dispute with those left in the IIC in Berlin about who had the authority to represent the Indian nationalists in Europe (Barooah, 2004).[4]

The history of the Berlin Indian Independence Committee not only offers insights into Indian anti-colonial movements outside the South Asian sub-continent and into German foreign policy strategies during the First World War. Members of the committee later found their purpose in various ideological, religious or political contexts. Recent studies that focus on the point of view of the different Independence Committees are now also examining the links between these committees beyond the strategic intentions of the Germans (Jenkins, Liebau, Schmid, 2020). In order to be able to systematically trace these histories, it is necessary to analyze further archival holdings of different national and political origins in India, England, Turkey, Sweden or Russia.

The concept for the German incitement strategy can be traced back to a memorandum prepared by Max von Oppenheim, the “Denkschrift betreffend die Revolutionierung der islamischen Gebiete unserer Feinde” (1914) (von Oppenheim, 2018) [Memorandum concerning the revolutionization of the Islamic territories of our enemies]. Shortly after the outbreak of war, Oppenheim had already pointed out to the Foreign Office the necessity of instigating anti-colonial forces through intensive propaganda campaigns, as well as financial and military support. He suggested the foundation of an institution especially geared to this purpose, the Information Service for the Orient. While, at a first glance, this appeared to be a translation and information office, it was in fact an institution of far-reaching propagandistic and intelligence significance. Here, strategies for propaganda were developed at various levels: in the colonies and dependent territories, among colonial soldiers at the front and in prisoner-of-war camps as well as in neutral countries. Relevant material was prepared, printed and disseminated in various languages. The NfO was staffed both by Germans (besides diplomats, also academics, missionaries, businessmen) and by representatives of the various colonised and dependent regions. Along with the NfO, Department III b of the political Section of the Deputy General Staff under Rudolf Nadolny was responsible for decisions and strategies in the sphere of propaganda. All activities thus took place with the approval and under the control of the Foreign Office and the Supreme Army Command.

“Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen in den Gebieten unserer Feinde. Indien” and other relevant file collections in the PA AA

The files of the 48-volume sub-collections WK 11f titled “Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen in den Gebieten unserer Feinde. Indien” (Undertakings and instigations in the territories of our enemies. India) belong to the R‑holdings of the Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, which include documents till 1945. These include papers for the period of August 1914-April 1920, which reflect German foreign policy efforts to promote anti-colonial developments in and with reference to India, the largest British colony. The documents comprise correspondence, reports and assessments, newspaper clippings, propaganda material as well as documents on administrative procedures. In their entirety, they give an overview of the work of the IIC and of the political activists associated with the committee, their positions, intentions and conflicts – viewed and filtered through the control and perspective of the German side.

Enquiries

For the first months of the World War, the documents deal firstly with enquiries about Indians willing to work with the German side. The Foreign Office obtained information about Indians living in Germany as well as from diplomats in different countries, for example in Switzerland. Indians like Chempakaraman Pillai, who lived in Zurich, or Abhinash Bhattacharya, who was studying in Halle, also sought contact with German government authorities to explore chances for cooperation. They gave further recommendations for contacts and assessed political activists who could be considered for membership of the committee. These assessments could be in the form of recommendations, but they could also contain warnings. Secondly, in the first months there are some reports about the situation in India. The central question was: How does the author assess the political situation, and does he see possibilities for carrying out anti-colonial uprisings in the country? The authors of these status reports were German businessmen, missionaries or academics as well as Indians who wanted to cooperate with the German side. In September 1914, Max von Oppenheim reported that “his” India Committee had been set up in Berlin.[5]

Correspondence

Furthermore, the files contain extensive correspondence between the Foreign Office in Berlin and various German diplomatic missions abroad, especially in Turkey, but also the correspondence between the IIC and the Foreign Office, between individual Indians and the Foreign Office. This correspondence concerned the organisational and personnel work, mainly regarding the question of propaganda and in relation to the various political-military missions in which representatives of the IIC were involved. The files also contain numerous documents on lengthy administrative and decision-making processes with reference to the preparation and execution of these activities. They deal with the logistics of the approach, including financial and personnel-related considerations that were discussed between the Foreign Office, the Department III B of the Army General Staff and various offices such as embassies, missions and consulates.

Reports

A further category of documents are the status reports, working reports, reports on surveillance of individuals and memoranda. The files contain, for example, several detailed reports about the work of the Indian Committee in Istanbul or on the so-called Baghdad mission and the futile attempts to establish an Indian Legion in Mesopotamia. From 1917 onwards, there are also reports from the Stockholm branch of the committee headed by Virendranath Chattopadhyaya. These reports, written by representatives of the Indian Committee, were commented upon by the relevant German authorities and provided with instructions for action. Some Indians were also placed under observation on the orders of the Foreign Office. Thus, Helmuth von Glasenapp, for example, investigated the scholar and revolutionary Shyamji Krishnavarma (1857–1930) living in Zurich, or sent reports about the lectures given by Chempakaraman Pillai in different German cities. The Foreign Office also generated separate files for some persons, for example for Chattopadhyaya. These are in the previously mentioned sub-files “Personalia” (R 21119-R21122).

Further Files

It is not only the India-related files in the holdings WK 11 “Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen” which provide information about the work of the Berlin-based IIC. There are references in the files on other countries, especially in those for Persia (WK 11e), Egypt (WK 11g) or Ireland (WK 11k). The IIC collaborated with representatives of these independence committees in various areas. Information about the propaganda work of the IIC among Indian prisoners-of-war is available under the file number WK 11s “Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen gegen unsere Feinde – Tätigkeit in den Gefangenenlagern Deutschlands” (Undertakings and instigations against our enemies – work in the prisoner-of-war camps in Germany). These files begin with the shelf-mark R 21244 in October 1914 and end with R 21262 in December 1919. The special work by some members of the IIC for the Information Service for the Orient (NfO), including the collaboration in bringing out the camp newspaper Hindostan in Hindi and Urdu, is reflected in the files of the NfO. The 27 volumes under the file number Deutschland 126 adh.1 begin with the shelf-mark R 1510 in January 1915 and end with R 1536 in December 1919.

Endnotes

| [1] | PA AA, R 21080, von Oppenheim in a letter accompanying a memorandum authored by Josef Horovitz discussing the situation of Indian Muslims, 11. March 1915. |

| [2] | PA AA, R 21070, telegram from the imperial envoy in Switzerland, Freiherr von Romberg, to the Foreign Office, 8. September 1914. |

| [3] | PA AA, R 21071, telegram from Freiherr von Wangenheim to the Foreign Office, Konstantinopel, 13. September 1914. |

| [4] | PA AA, R 21111, report of the Indiske Nationalkommittéen in Stockholm addressed to the Indian Committee Berlin-Charlottenburg, 17. January 1918. |

| [5] | PA AA, R 21071, note from Max von Oppenheim to Otto Günther von Wesendonk, 11. September 1914. |

Secondary Literature

Barooah, Nirode K., Chatto: The life and times of an Indian anti-imperialist in Europe. New Delhi, Oxford: OUP, 2004.

Bihl, Wolfdieter, Die Kaukasus-Politik der Mittelmächte. Teil 1: Ihre Basis in der Orient-Politik und ihre Aktionen 1914–1917. Wien: Böhlau, 1975.

Bose, A. C., Indian revolutionaries abroad: 1905–1927. New Delhi: Northern Book Centre, 2002.

Conze, Eckart, Das Auswärtige Amt: Vom Kaiserreich bis zur Gegenwart. München: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2013.

Fischer, Fritz, Griff nach der Weltmacht: Die Kriegspolitik des kaiserlichen Deutschland 1914–1918. Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag, 1984.

Fischer-Tiné, Harald, “The other side of internationalism: Switzerland as a hub of militant anti-colonialism c. 1910–1920”. In: Patricia Purtschert and Harald Fischer-Tiné (eds.), Colonial Switzerland: rethinking colonialism from the margins. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 221- 258.

Jenkins, Jennifer, “Fritz Fischer’s ‘Programme for Revolution’: Implications for a Global History of Germany in the First World War”. Journal of Contemporary History 2013, 48: pp. 397–417.

Jenkins, Jennifer, Heike Liebau and Larissa Schmid, “Transnationalism and insurrection: independence committees, anti-colonial networks, and Germany’s global war”. Journal of Global History 12, no. 1 (2020): pp. 61–79.

Liebau, Heike, “The German Foreign Office, Indian emigrants and propaganda efforts among the ‘Sepoys’”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds.) ‘When the war began we heard of several kings’: South Asian prisoners of war in World War I Germany. New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 96–129.

——–, “Das Deutsche Auswärtige Amt, indische Emigranten und propagandistische Bestrebungen unter den südasiatischen Kriegsgefangenen im ‘Halbmondlager’”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau, Ravi Ahuja (eds.) Soldat Ram Singh und der Kaiser. Indische Kriegsgefangene in deutschen Propagandalagern 1914–1918. Heidelberg: Draupadi Verlag, 2014, pp. 109–143.

——–, “Hindostan – a camp newspaper for South Asian prisoners of World war One in Germany”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds.) ‘When the war began we heard of several kings’: South Asian prisoners of war in World War I Germany. New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 231–249.

——–, “Hindostan. Eine Lagerzeitung für südasiatische Kriegsgefangene in Deutschland 1915–1918”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau, Ravi Ahuja (eds.) Soldat Ram Singh und der Kaiser. Indische Kriegsgefangene in deutschen Propagandalagern 1914–1918. Heidelberg: Draupadi Verlag 2014, pp. 261–285.

Loth, Wilfried, Erster Weltkrieg und Dschihad. Die Deutschen und die Revolutionierung des Orients. München: Oldenbourg Verlag, 2014.

Lüdke, Tilman, Jihad made in Germany: Ottoman and German propaganda and intelligence operations in the First World War. Münster: LIT, 2015.

Manjapra, Kris, Age of entanglement: German and Indian intellectuals across empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Purtschert, Patricia, Fischer-Tiné, Harald (eds.), Colonial Switzerland. Rethinking colonialism from the margins. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Oesterheld, Frank, “‘Der Feind meines Feindes ist mein Freund.’ Zur Tätigkeit des Indian Independence Committee (IIC) während des Ersten Weltkrieges in Berlin”. MA Thesis, Humboldt University Berlin, 2004.

Oppenheim, Max Freiherr von, Denkschrift betreffend die Revolutionierung der islamischen Gebiete unserer Feinde, herausgegeben von Steffen Kopetzky. Berlin: Verlag Das kulturelle Gedächtnis, 2018.

Zürcher, Erik-Jan (ed.), Jihad and Islam in World War I: studies on the Ottoman jihad on the centenary of Snouck Hurgronje’s “Holy War made in Germany”. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2016.

Heike Liebau, Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029